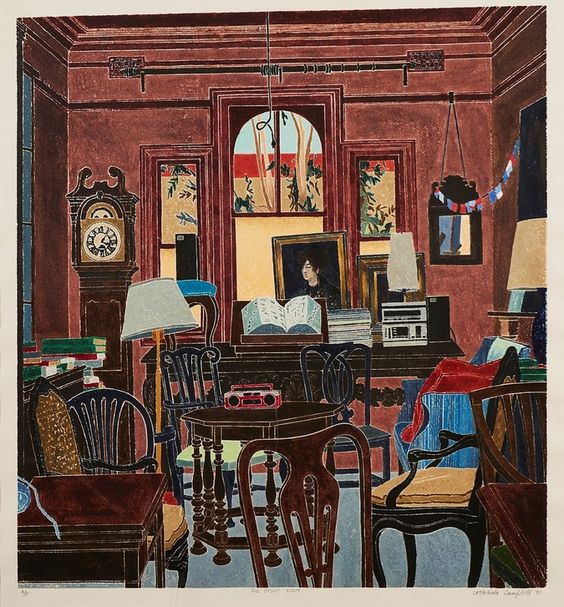

This is the image that remains stored in my memory.

The apartment smells lived in and comfortable even before we move in and unpack our furniture. The floors and walls are often hard to tell apart; they are an unsettling shade of white that makes me want to be freshly showered at all times. It is the perfect size for the three of us. The building is placed on a street that looks as though an adult played with a Lego set: each house has been set down exactly where it should be, and the trees are tucked in between symmetrically.

I decide that I will become a writer in this apartment. But first, I become a fashion designer and an artist, collecting scraps of paper in a bag that hangs on the side of my bed. I start scrapbooking and spend too much time poring over the characters inside Roald Dahl’s stories. His words are always having fun even after the story is over, and I am afraid that my own writing will remain stagnant even when the book is closed. For a while, I stop reading because it scares me.

Mai gives me two flowering plants after the cardboard boxes are finally emptied. In the weeks that follow, I forget to water them, and they die. The soil is disposed of, the pot recycled. When odd things happen after their unfortunate death, I start to wonder whether it was my negligence of nature that caused them.

There are three bedrooms. They sit cross legged next to each other.

*

Sometimes, I sit in the study and listen to my father typing. The click-clack sound of the faded black keys on his laptop always cause me to tear my eyes away from The Famous Five and try and read the endless rows of text on the screen in from of him. His oily skin glistens in the lights cast on his face from the laptop, his fingers fly across the keyboard.

Someday, I will learn to type with both hands, without looking at the letters below them.

Papa’s mind is an oddly shaped object. It reminds me of the strange figures printed in math textbooks, the ones that are placed innocently on thin pages to confuse you and make you fear numbers. I do not fear him, but rather, the thoughts that swim below an overly polished exterior. He looks up at me and smiles, but he is a million miles away.

The study was decorated with artificial care. Green leather armchairs face the rosewood TV stand and in between them is a desk that has nine drawers, stuffed with stacks of paper I am not allowed to touch.

When I become a writer, my desk will be just like this one, with a leather swivel chair and gold fountain pens in a turquoise pen stand. The surface won’t have any dust or old bills littering the corners, but instead, the moleskin journals I carry every time I go to a coffee shop to observe people. Bookcases will line each wall, and in the corner, a single armchair the colour of a broken pomegranate will sit solidly, like a buoy in a sea of wood.

For now, I settle for a blond table in the corner of my bedroom that has a wonky drawer and a cupboard with a broken shelf.

*

The master bedroom is much more exciting than my own. The walls are the colour of olive oil and Tuscany, and the bed is always made. Ma hates the Aboriginal snake painting on the wall; she thinks it is bad luck. Someday, I will write an essay about a python who is sad because he can’t ride a bicycle, but goes on to become the director of Tour de France.

From my vantage point on Ma’s balcony, I watch Manjula with fascination each day. She is the elderly lady that lives in the building next door. Our apartment is on the first floor and hers is on the second, and I watch her watch TV every day. Her right arm cushions her head when she stares unblinkingly at the screen in front of her. She gets up periodically to drink water and eat a banana, then drops the peel into the car park below. Her saris are always neatly tied, like she is expecting company at any moment. From the looks of it, she lives alone.

I am 11 years old, and my preteen mind finds her loneliness amusing.

Every morning, she stands on her balcony and sings to the crows. Her voice is high pitched, the kind that can cut right through suburban silence. When she peers into our kitchen, we learn how to stop staring back. Her family rarely visits, and five years later I realise that we were probably the closest substitute for the one that no longer cares about her.

When watching her quickly becomes dull, I use an old notebook and start to write down all the mediocre stories that are in my head. I promise myself that Manjula will become a supporting character, the carpet in the bedroom of my mind. Years later, when the apartment becomes someone else’s, I find that there are new houses full of people to observe. Those families shriek at each other at 6:00am, and I forget what her silence looked like. I continue to write on Ma’s bed; it remains tidy and dust free, and I learn to listen for the sounds of characters coming to greet me.

Later, when I turn 20, I will come to regret making fun of her loneliness, for it was probably all she had left behind.

*

Shanthi Akka comes home every day to clean. The steel dishes are scrubbed with vigour, like she is fighting a war against herself in the sink. I barely make contact with the kitchen while she moves around in it, because I am afraid of yanking apart the silence that she creates.

Her eyes always have shadows under them. She teaches me how to let Kannada syllables roll off my tongue with ease, and every time she holds my textbook, she stands a foot away from me, her voice never louder than a whisper. I am failing third grade Kannada in the 6th grade, but I push myself and memorize a poem about sunrises and chickens, and end up coming first in a recitation contest at school. Grace ma’am smiles smugly to herself, as though she is congratulating her teaching skill. I have Akka to thank.

When I watch Viola Davis bring Aibileen to life in ‘The Help’, I want to look at my world through her eyes. What do the spaces inside our apartment look like to her? Does she tell her daughters stories about the time Ma caught me talking to my toys, and I fell off the bed in embarrassment? Are our curries bland and unappetising? Does she ignore the weird silences between my parents when they refuse to speak to each other, or is the apartment always too quiet to realise the absence of noise?

She is asked to dust the bookcases every alternate day. The shelves are dotted with finickily placed knick-knacks and framed photographs, the wood is the colour of a naked tree. Each time she coaxes dust out from underneath the bed, I can’t help but feel a sense of shame, and guilt. If life had dealt me an entirely different sets of cards, I might be the one going home and telling stories about the eccentric family whose home I worked in every day.

When I catch her wearing my scrunchies and clips, and pocketing my junk jewellery, I am furious. Several years later, I come to make peace with the fact that even though taking what is not yours is wrong, it might be all you have left.

The tapestry of our family life was woven with threads that are wearing thin. She is in the background. It just isn’t one that hung out anymore.

*

The branches outside my bedroom window prevent me from temporary blindness when I wake up each morning, and instead, the sunlight casts strange shadows onto my bedroom floor. (Ma tells me I spend far too much time in my room, reminding me that my pink cycle is parked downstairs. Underneath a fire extinguisher is a two-wheeler that is supposed to be the defining object of my childhood, but there is no one to go cycling with. Inside my head, my legs are toned, my hair is sun bleached and I am the brown version of Nancy Drew, traveling around Fraser Town, solving crimes on a bicycle without trainer wheels. It is stolen when school reopens, and I give up trying to have fun outdoors.)

My father travels extensively on work, and there are long stretches of time when I don’t see him for several weeks. The apartment becomes messy without him around: we leave piles of clean laundry in the living room and adjust to the comfort of untidiness. In his absence, we find ourselves speaking louder, almost as though we forget to miss him. But every time I look up at a cloudless sky, I imagine that he is looking at the same one, believing that nature is tying us together with worm-eaten leaves and pieces of wind that disappear as quickly as they arrive.

Seven years later, I will start to travel to places alone. My head attempts to rest against the bus windows, constantly hoping that once I am able to look past the men spitting paan onto sidewalks, I will see a sky so perfect, that he will be looking at it too.

Unfortunately, the sun only makes me squint.

*

Before we move in, the apartment smells comfortably lived in, like a bedsheet used by every generation in a family. On the day we move out, I realise that there was too much furniture in it for the three of us. When the packers and movers take a break for lunch, I whisper a goodbye to each room. The walls are stained with the outlines of our family stories. Manjula is asleep when I shut the front door behind me. Papa is still traveling. Ma’s smile is tired and there is packing tape stuck to the seat of my sweatpants.

I decided that I would become a writer in that apartment. My publishing deal hasn’t come through yet.

Featured image credits: Pinterest, artwork by Cressida Campbell

Amelia David

Latest posts by Amelia David (see all)

- “It all comes back”: On Reading Joan Didion - 7th July 2020

- Udupi Is Only a Five-Minute Walk from College - 16th August 2019

- #101 - 26th May 2019