Back home in Mangalore, where the city is quickly eating into the few remnants of the nostalgic town that once was, I spotted a house that was consumed not by the glassy steel of modernity but by wood and leaves.

After acquiring a heart problem, my grandfather has taken to walking. In keeping with the family tradition he’s flown in the face of any medical advice and decided he needs to walk about 7 kilometers every day. He likes to cover the entire city going from Pumpwell to Bendorewell to Karangalpady to Lighthouse hill.

‘Yenchina? Mangluruu travels a?’ my mother complains.

My grandfather and I would have gone about our evening walk together in silence if he hadn’t pointed out that little plot of green. This was one of the city’s lesser cluttered back alleys that leads to the district court, where empty plots draped in sunshine and grass, hosted cricket games with concert wickets. If they couldn’t find a good section of the wall they’d prop up a granite slab- because there are always granite slabs lying around in those empty plots hoping the slabs didn’t fall over when the umpire had to make a call.

Children in uniforms, teenagers eager to escape the hostels and middle aged men share the field. Empty plots in these areas weren’t an unusual sight. All the age groups seem somewhat familiar with each other; they stuck to their own games but some of them would greet each other.

‘Encha Ulla?’

‘Yaan Aarama. Enchina Vishesha?’

A few kids hanging around snorted as the teenager tried out his weak Tulu and the man with the mustache smiled awkwardly.

‘Look at that house there’ said my grandfather.

‘Yeah?’

‘Know it?’

‘Nope’

‘Yenchina? Louder! Louder! It’s an old house. These people are doctors who get their children educated. The children go abroad and don’t want to come back. The parents have nothing to do here, so they tell their children they’re going to move there. They leave the houses behind and everything falls apart.’

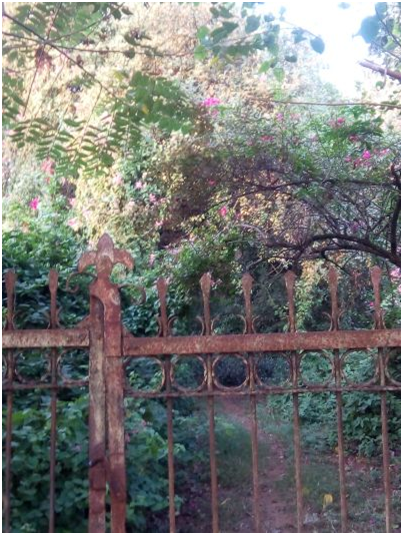

My grandfather was referring to the old wealthy residents who left the city a generation ago. The abandoned plots hosted decaying mansions and overgrown trees while the city’s residents grew faster and busier. The sudden drop off the road leads directly to the house, which must have once been impossible to miss.

‘See the walls?’ my grandfather asks, arm pointed forward like he was signaling some obscurity in the horizon.

‘It’s like all the old Christian houses. The compound walls become part of the house. It’s always like that; they always have to have the wall… and a well and a chicken coop. They always build it like that. Nice isn’t it?’

But now it’s the new trees and blooming plants that guard the house. They choke every inch of free space, and entry is impossible. A few curious branches have already begun to climb in through the thick glass windows. Maybe they want to know about the old residents too.

‘Do you know who they were?’

‘Hmm?’

‘Did you know them?’

‘He built a nice house. I was very young when I was here, this used to be the outskirts of the city you know. Imagine how much my mother’s house in the city would have been worth if she hadn’t sold it.’

‘Did it look like this?’

‘Most houses did. I’ll show where it was on the way home’

The gate seemed funny, why would you need one when the house is impossible to access? Do the forests need walls to protect them from the city now? If you looked through it you would see a bit of forest, guarded by the red brick compound wall, in the few remains of the old town.

‘Careful. Broken glass there. We should go anyway. I’ll show you other houses on the street. They’re on the way. One of them has a roof that’s just started to cave in’

My grandfather seemed to walk a more relaxed pace; he stopped stooping as he walked. He interrupted his thoughts and asked if he’d ever told me about the ancient living room size Fords and Buicks the family used to own.

Standing with our little glasses of sugar cane juice, I ask him if he misses the old city, he shrugs and says he’s just reminiscing. Mangalore isn’t his home; it is just a place he remembers. He stops talking as much. Maybe he was tired; his rounds of the city always involve climbing Mangalore’s steep hills. Getting him to tell you stories is always a hard task, even though he excels at them.

He laughed and complained about the traffic in Mangalore and how he used to be stronger than a twenty year old until he caught malaria last year. Conversation with him is always spontaneous. I don’t remember much of the walk home. Just the blaring traffic and cement buildings. We didn’t say much, he was thinking to himself and occasionally thinking out loud. A habit the entire family has picked up from him.

When we reach home he says he’s tired and goes to sleep right away on his plastic chair, but not before telling me to wake him up if there’s Mixed Martial Arts on TV. He likes watching it and often complains about WWE and how fake it is. It’s the only thing he still watches on TV and then when he’s bored, he walks.

Rijul Ballal

Latest posts by Rijul Ballal (see all)

- Taking Mahaquizzer - 22nd January 2017

- Overheard at the ATM - 29th November 2016

- ‘ಪೋಕೆಮಾನ್ ಗೋ’ (Pokemon Go) - 1st September 2016

Krishna Kinnal 8th March 2016

Where exactly in Mangalore is this house at?