‘I feel no nostalgia for our childhood: it was full of violence’

Among the many things that Lenu – the narrator of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series says, this is the one thing that I keep going back to. I am puzzled by her clarity. Our childhood she says. The ‘I’ already forgotten. I is what memorable stories begin with and in My Brilliant Friend, the I is strong enough to remain invisible and vulnerable enough to tell the story of an ‘our’.

And soon we learn that this is not a challenge for Lenu, or Ferrante, to continue a struggle that began in childhood and keep it going until the last page of the series. It’s a habit.

In the beginning of the book, Lenu finds out that her friend Lila has disappeared. They are both 66 and I giggle a little when she says, ‘Lila is overdoing it, as usual.’ As if the three of us have been friends for a long time.

This is the first thing we learn about Lila. That she overdoes. And so Lenu decides to overdo it too and begins to write their story- from the beginning, about everything that she remembers- to see if she can bring her friend back.

But now I have decisions to make. How do I read this book if it is going to enact my life out to me? I am not even two pages into the book and I have already become the third wheel – I am neither Lenu nor Lila. I am the third person who can never be their friend. When Rani and Preity danced to Piya Piya in yellow towels, there was no room for another woman. It is always in twos – that’s the rule – Jai & Veeru, Laurel & Hardy, Tom & Jerry, Batman & Robin and the two and only – Dingo & Khanna.

This is my tragedy.

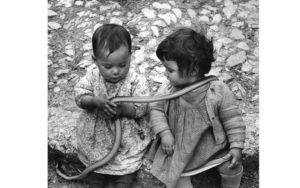

Two children with a snake. By David Seymour, Italy – 1951

***

The third book in the Neapolitan series is called ‘Those who leave and those who stay.’

I am reminded a little of all my third wheel friendships. In the first, one of them told me to leave them alone for a while because they had private things to discuss. The second – one of them said she wanted to put me in a mixie and grind me and then stomped off, the other one running after her. The third, and the most boring of them all- they wanted me out so they could be closer to a man.

The only gift that these dabba friendships gave me was that I discovered the voyeur in me. And for good reason. They were each preparing me for the ultimate voyeurism treat which was to read the story of Lila and Lenu.

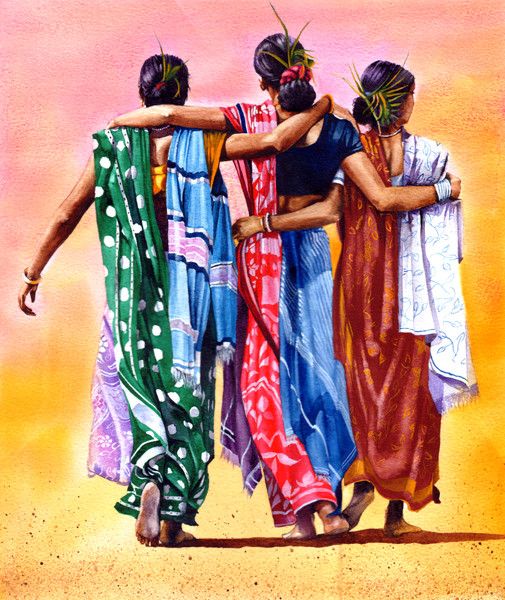

Friendship by Peter Wiliams. Via ArtWanted.

In chapter 2, Lila and Lenu have exchanged dolls and are sitting by the window of a very scary basement. And then Lenu says –

And so, on the day that Lila and I exchanged our dolls for the first time—with no discussion, only looks and gestures—as soon as she had Tina, she pushed her through the grate and let her fall into the darkness.

I am made aware that there is nobody meaner than little girls who have become best friends with each other. And they become friends not because they like each other, not even because they hate each other, but because they know that they deserve each other more than anybody else.

And so Lenu also throws Lila’s doll into the basement. What you do, I will also do.

There is a maniacal fearlessness in this moment. They have only each other in that wretched neighbourhood. It’s a risk I’d never take with someone I wanted to be close to. I’d never throw their dolls, even if they threw mine.

Lila however has no fear. Lenu, in a strange way, also has no fear in the way she allows Lila to take over her. I hadn’t expected a bunch of four year olds to have this much power over me. They scared me: more than the loud guffaws of men, more than my mother’s face when I sneak home late.

We take great pleasure in watching the things that we are most afraid of.

Months after the doll episode, they are returning from school one day, when a fight breaks out between Lila and the neighbourhood boys. When I say fight, I don’t mean the cute dishoom dishoom that we see in ads. Fight maane fight. Full on stone pelting. And Lila is relentless in retaliating with bigger, sharper stones. Lenu wants to leave but cannot. In her words, ‘Already then there was something that kept me from abandoning her. I didn’t know her well; we had never spoken to each other, although we were constantly competing, in class and outside it. But in a confused way I felt that if I ran away with the others I would leave with her something of mine that she would never give back’

At this point, I am both afraid of Lila and very much in love with her. And at this point, I am afraid for Lenu and want to tell her to run.

This dilemma of whether to keep walking or to turn back – to leave or to stay is an unsettling one – for lovers and friends alike. Everything seems to be decided in that one moment. And what we decide, we become. Let us all take a moment to remember Lot’s wife here.

In my favourite scene from DDLJ, Raj knows that if Simran turns back to look at him, it means that she loves him. Palat, palat, he says until she finally looks back at him and smiles. This is how Raj (and also we) finds out that she has fallen in love with him.

In the few friendships that I have had with women, sometimes I turned back and sometimes I didn’t. Either way it didn’t matter because they were neither turning back for me nor walking away from me. Lenu always turns back and Lila never does. And this, I believe is their tragedy.

***

Our worst fear is that someone is always better than us even without the privileges that we have. Let me be fully modest and rephrase that – My biggest fear is that someone is always better than me even without the privileges that I have.

It’s only natural that when Lenu is allowed to go to Middle school and Lila isn’t – Lila makes sure that she is still better. And so Lenu is forever wondering how Lila is able to learn Latin before her, how she is able to write so well and read faster and better than her.

Years ago, they’d both acquired an old copy of Little Women. They spend days reading it aloud to each other sitting in the middle of the street. And there they decide to write a book together and even before Lenu can understand it, 8- year- old Lila writes a book all by herself. It’s called The Blue Fairy. Lenu reads it and is never able to recover from Lila’s writing. Everything she writes from then on is for Lila. Lila defeats Lenu when they are only 8 and Lenu spends the rest of her life catching up with this moment.

And so even before she begins writing the series, Lenu tells us, “We’ll see who wins this time”

We don’t know what’s in The Blue Fairy. We know Lila’s writing only through the one letter she has written for Lenu.

It was a letter from Lila. I tore open the envelope. There were five closely written pages, and I devoured them, but I understood almost nothing of what I read. It may seem strange today, and yet it really was so: even before I was overwhelmed by the contents, what struck me was that the writing contained Lila’s voice. Not only that. From the first lines I thought of The Blue Fairy, the only text of hers that I had read, apart from our elementary-school homework, and I understood what, at the time, I had liked so much.

There was, in The Blue Fairy, the same quality that struck me now: Lila was able to speak through writing; unlike me when I wrote, unlike even many writers I had read and was reading, she expressed herself in sentences that were well constructed, and without error, even though she had stopped going to school, but—further—she left no trace of effort, you weren’t aware of the artifice of the written word.

I read and I saw her, I heard her. The voice set in the writing overwhelmed me, enthralled me even more than when we talked face to face: it was completely cleansed of the dross of speech, of the confusion of the oral; it had the vivid orderliness that I imagined would belong to conversation if one were so fortunate as to be born from the head of Zeus and not from the Grecos, the Cerullos.

I was ashamed of the childish pages I had written to her, the overwrought tone, the frivolity, the false cheer, the false grief. Who knows what Lila had thought of me? I felt contempt and bitterness toward Professor Grace, who had deluded me by giving me a nine in Italian. The first effect of that letter was to make me feel, at the age of fifteen, on the day of my birthday, a fraud. School, with me, had made a mistake and proof was there, in Lila’s letter.

***

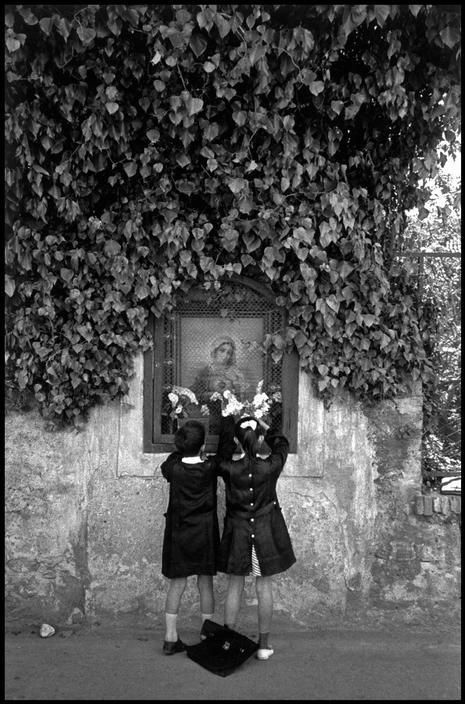

Sicily – 1961. By Bruce Davidson.

I have never read anything like this before. I don’t know many books that can be so shameless about their own vulnerability and in their obsession with women – one woman. This is how I want to be written about – this is how I want women to be written about.

I can now only make the effort to write about reading Ferrante through the pangs that have been thrust upon me through Lila and Lenu.

Those two will stay with me for a long time. Lila, because she has the capacity to be aloof, alone, anywhere. You can trust her to make you feel like you are the most important person in her life one moment and a complete stranger the next. She will look at nothing in particular when you are with her and you will wonder if she is enjoying a private world in her mind that you know nothing of. You will come to understand that aloofness as a betrayal. Your achievement is your intimacy with her and your tragedy is that she knows it and doesn’t care. It’s beautifully devastating that this struggle is between two women and not a man and a woman or two men.

Lenu will stay with me longer because she isn’t afraid of her tragedies in the way that I have been taught to be and in the way that Lila sometimes is. She has embraced it and written four books about it.

***

A question that plagued most friends after they finished the book is whether they are Lenu or Lila. One admitted to have had the same anxieties that I did while reading the book because she was scared that she was Lenu.

I understood what she meant. We can’t help but wonder. Isn’t it a nightmare to allow one person to determine the course of your whole life? My only hope, if this nightmare is real and I’m sure it is- is that I wish all my Lilas are women.

I spent the last two days devouring YouTube interviews of women that I really admire, paying close attention to the way they sat, wore sarees, spoke, the way they moved hair out of their eyes and my stomach felt warm.

Over the years, after tiresome third-wheeling, I have learnt to be distant. I watch these women from a distance and now have many Lilas.

In the fourth standard, there was a Lila in my class. Her name was Gaana and we were all besotted with her. One girl, in particular, began imitating her- everything, from the way she sat, wrote, to the way she ate, listened and walked. Another girl got very jealous and when she could no longer take it, she declared loudly to the class teacher, “Miss, this girl is copying everything that Gaana is doing, miss”

I immediately froze since I was under the impression that I was the only one imitating Gaana and when I realized that they were all doing it, I stopped.

***

I wailed bitterly and loudly into a pillow after I finished the last book. It’s not every day that I witness something that dangerously puts together the stuff that both my nightmares and dreams are made of.

Whether or not Ferrante is Lenu, is actually a man, or doesn’t exist – I don’t care. Because she has taught me that it doesn’t matter how I write but that I must. That I can always rely on writing to bring my Lila back or chase her away.

Dingo and Khanna. Taken from Youtube.

When I was beginning this piece, I struggled to think of a female duo. A lot of time passed from Batman &Robin to Dingo& Khanna.

I first met them in the dingy toilet of a Mumbai local train. One was rolling and the other was figuring out ways to deal with her mansplaining boss. This wasn’t a familiar sight but it was not hard to imagine that they exist. Between Lenu-Lila and Dingo-Khanna, there is a world of difference. If D&K met L&L, I think there would be more eyes rolling than any other rolling. I am not sure this passionate love-hate between friends is something they’d approve of. Much as I hate to admit, I do want more D&K love than the L&L uncertainty.

***

TransFerrante – Meta 2017

Even after having dragged My Brilliant Friend to all my classes and imposing it on students this year, it still felt strange to not have a panel about it at Meta. The evening that we decided on the panel, I began making loud poster-plans. ‘I have an idea,’ I announced. ‘I’ll put Elena Ferrante’s photo right in the middle and…’ Needless to say, I would have carried on if it weren’t for the wide grins that surrounded me.

On the panel were my favourite women from 2017.

Picture by Nandita Raghunath. Ila, me, Drishti, and Vismaya. TransFerrante, Meta 2017

Thirty minutes before it began, we were all feeling collectively harassed. When the moment arrived however, I felt strangely cut off from the audience and everything that I had to say I wanted to say only to the three women sitting next to me.

And then the panic just dissolved because talking to these girls felt like a very natural way of book-ending the Ferrante season.

What I took away that day from the panel is that there are a lot of people who will find it strange and unnecessary that you love something unapologetically but what other way to love is there?

Latest posts by Vijeta Kumar (see all)

- It was supposed to be Pascal’s Triangle but you two came - 2nd December 2024

- A review of Mother steals a bicycle and other stories - 17th November 2018

- What happened when Bengaluru’s working class women had a #MeToo meeting? - 7th November 2018

Dee 18th June 2021

Why is everything that you write, so utterly beautiful. Cheryl Strayed wrote once that one must write like a mother fucker to get that one book out of your system. I think you do it on all days.