When I heard it said that Brahman Naman was a film about quizzing in the 1980s, I wondered if it would slide under some available template: scandal below super-clean surface as in Quiz Show, or worse still life-lessons & love bhelpuri of the Starter for Ten variety. I was pleasantly surprised to see the film manfully avoid such temptations.

It’s not really a film about quizzing, though the pastime does give it some of its shape. If anything it is a bunch of sketches lashed together in acrid black humour, in which general and carnal knowledge are alternating elements. The characters are offered little by way of redemption; irony and satirical purpose seem to snap at their heels unceasingly and reduce them somewhat.

The obscurely desired cinematic object here is Singh-Singh—the liminal period, roughly 1984 to 1996, between two liberalisations, or two Finance Ministers (VP and Manmohan)[1]. I’ve heard some people pull the word nostalgia and wave it about in conversation, but the film is remarkably dry-eyed and matter-of-fact in this department. There is perhaps some other species of curiosity at work here–something of an out-of-the- corner-of-the-eye way of looking at history rather than overt nostalgia.

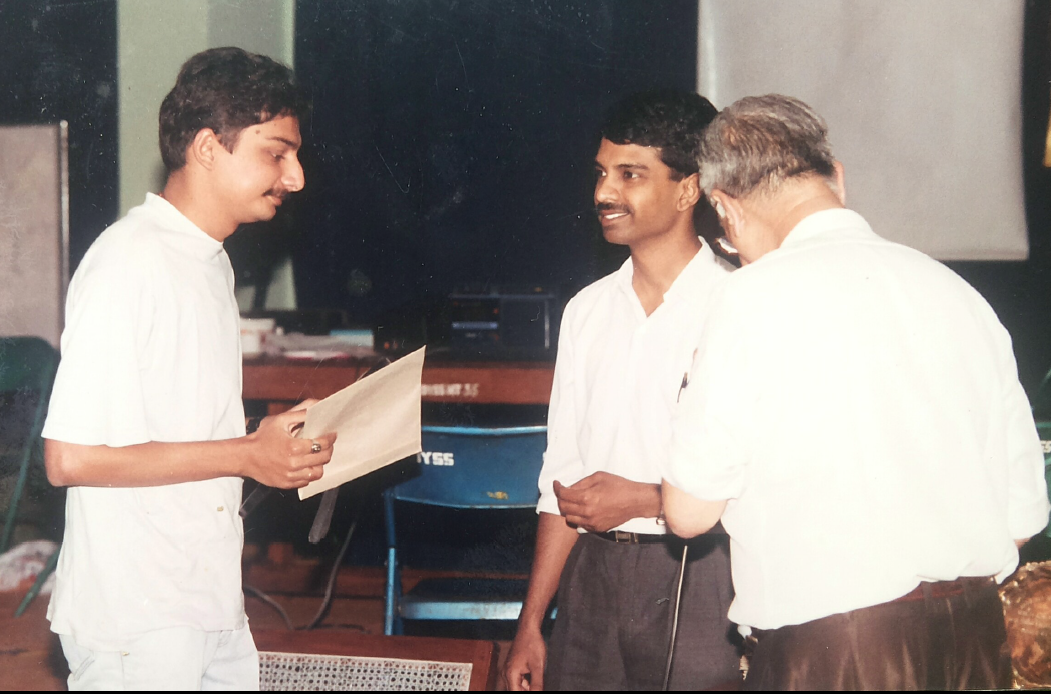

An unusually bashful Naman in 1993

The nostalgic eye will nevertheless notice enough that has disappeared to grow misty-eyed over. The smuggling-like process for acquiring Debonair. Bangalore was open city then–people smoking freely in public places[2], and drinking[3] at joints that may not have had liquor licenses. Open in another way too—for it was then a half built-up city with vacant lots, and empty roads. The Mysore locations replicate very carefully an Indiranagar light, a skittery, cheery almost-American brightness, unimpeded by buildings because everybody built their houses in measured civic-mindedness. At one point, Ajay and Naman go around a huge tree twice on scooter as if to emphatically announce the camera’s delight at having found a tree-circle exactly like the one off CMH Road. The bench that the boys sit on is a replica of the Bank Club, a bench on 100 Feet Road, outside Syndicate Bank, where Naman and his friends held their darbars with neither traffic nor vehicle noise to worry about. The closing moment of the film has them on the bench, no dialogues, and you can hear crows and what might be a sparrow.

Suchitra Film Society’s auditorium and one arm of the arcade at St. Joseph’s Evening College stand in for Guru Nanak Bhavan and SJCC—one building is no longer available as quiz venue because NSD-Bangalore uses it, while the other has been replaced by a modern building.

***********************************

Sometimes we have to plunder shamelessly from other languages to be able to account for vaguely untranslatable feelings. Especially those that seize us when we are watching something from our time, when we look at the half-forgotten and wonder if we should say something whilst those experiences are swept away before our eyes into the cinematic.’

The word to filch while watching Brahman Naman is the emotional Arabic term biladi, meaning ‘my country’, or more simply, ‘my land’ or even ‘namm-yarea’. Bangalore quizzing from the late 1980s is possibly the only kind of biladi that feckless users (or vice versa) like me can lay claim to.

And so I began watching the film, back upright so as to allow the obligatory lump in throat to form efficiently whenever. Something else happened, however, as the very first frame of the film hove into focus. It had the standard flute dedic-bgm that goes with photographs of the respectably defunct and professions of undying gratitude to those r.d. But the thing bristling between the melliflutes and the mallipoos was no portrait, just a long quote signed Naman. It was vaguely familiar, and it began with the words “All said and done, the young male, anywhere in the world, is a rather ugly and pointless evolutionary experiment.”

As the film began to lavish its various goodies on my soul, I began to grow lightheaded. A little from its antic revisiting of the past, but more from the simple frustration of not being able to place the author of that darned quote. Eventually, my head wilted like it was a long-stemmed roja from all this futile memoriousness. I paused the film and began doing various anti-Alzheimer[4] exercises furiously.

In the interests of poetry, and truth, these are respectively: clench your left fist into a ball and let go, repeat same with right, bring your toes down on the floor like you are playing a giant tabla, move the muscles around your face in random order, go to the loo, drink water, swear properly in Kannada, and so on. Nothing worked. I went back to watching the film.

All this effort, sadly, only got me a lot thirstier. I went to fix myself a wry little measure of Russian culture[5]. Something about the comforting ritual of getting little cubes of ice to meet their brother molecules from the steppes sent a surmise down long dormant neural circuits. I then knew where the quote was from.

Problem solved, I went back to watching the film, and liked parts of it. On the second and third viewings, I enjoyed the film much more. Possibly because the evening’s Russian presence had begun to Bolshoi inside my head. So I watched it again, the next day, unaccompanied by foreign persuaders. Then I read the reviews. And laughed—at the reviewer monkeys who went I used to be a quizzer, but now I’m better. And watched it one more time in protest and solidarity while the Russian in the glass and the Russian in my belly murmured the word Mir[6] to each other many times.

Here are the bits of enlightenment that set me at rest. Once upon a time, Russian culture was the necessary prelude to every attempt I made at blogging. The rascal script-writer had maro-ed the film’s epigraph from a post I had written, while being loyally Russian, about my many attempts at watching Hi Fidelity. He had even told me that he was going to maro said line. I had said hanh-hanh and forgotten. While watching the film I went from cosy biladi to biladi phule but Russian culture jogged my memory and saved me. Where would I be without Russian culture?

You can read the quote in all its hirsute non-glory, if you want to, here.

**********************************

I met Naman[7] in 1985. In a sudden departure from the normal practice of picking those who were ‘good in studies’, our school had held a written GK test (‘Who wrote India Wins Freedom?’)[8] and thrown the top three together. That was how RS Naman, self and one MV Sundararaman found ourselves rattling along with the school librarian on a Saturday in August ‘85 in a double-decker 131 to the St. Joseph’s Indian High School OBA quiz. The stiff silence in the near-empty bus was broken only by noises of animal ecstasy as its articulated mechanism ground laboriously to a halt at each of the eight stops between our school and the venue.

At the quiz, conducted by SJIHS alumnus and City Tab[9] columnist S. Shyam Sundar[10], we made it to a tie-breaker for the last place in the finals with four other teams. We had scored 5 and 5/8 and I had contributed two to the score—the fraction coming from some list-type answer. Of the two, one was a question that went ‘What is bruiting, usually considered an offence in national emergencies?’ I had seen the question in my copy of the Bournvita Quiz Book, but couldn’t remember the answer. Having never considered the possibility that I might need to remember it someday[11]. I also knew the word because it occurred somewhere in the Bible and from there arrived at the laborious answer ‘to say bad things about the government’. The answer, when it came out to war-cries and banshee noises from girls and boys alike, was ‘rumour-mongering’. Somebody had mercifully given us points.

We went up for the tie-breaker, got one right out of the three questions, and got knocked out. The librarian said I was so proud when they announced our school’s name on the mike. Then, in the same breath, she said I have to go and left. We caught a bus home, discussed the prelims threadbare and agreed to tell the other teachers that we had got knocked out in the semi-finals. Honesty is always the best policy, but when you have to be your own insurance agent, you have to know when to put some careful English. We were kept on in the school quiz team and did much better in our next few outings.

Naman finished school that year and joined St. Joseph’s College of Commerce (the St. James in the film) for PUC, and then a B.Com degree, and finally a PG diploma in Business Management. I joined PUC in 1987, and dug myself into college quizzing from that moment on till I completed my MA in August 1994, for a full seven years. For some of that time, we were quizzing rivals because I studied at Christ, and there was then much bad blood between our colleges around the sports fest Spiel. Naman had founded a Saturday afternoon quizzing outfit called Metaquizziks in 1989 with his SJCC team-mates Ashwin[12] and Raju[13] because they never qualified for finals and felt the need to ‘improve’. I was allowed to join, but only after much begging and a one-hour debate among the founders over the wisdom of allowing traditional rivals Christ to benefit from an SJCC venture.

MQ Meetings[14] began at an asbestos-roof tuition joint above Lakshmipuram Bus Stop, dubbed ‘the cowshed’, that was somehow free on Saturday afternoons. They eventually moved to Naman’s flat, where the high point would always be the audios played off his Sonodyne Uranus system, a squat lowering beast that combined LP, CD and tape decks with divine sound. At some point Naman got a letter-head printed for The Metaquizziks Society (Address: his flat; Motto: Veni Vidi Vici[15]) with all our names running down the left-hand margin. We ‘improved’, but were never good enough to beat the best college team of those years—N. Kiran[16] and M. Suresh[17] of BMS College of Engineering.

In May 1992, Calcutta was celebrating their 25th Anniversary of quizzing (17th in the film, for occult reasons) and invited KQA to send a four-member team to take part. Questionable Characters, led by the then unbeatable GS Hiranyappa[18], with Suresh and Kiran, would have been the automatic choice, but the last-named was unavailable. Naman was a shoo-in both on account of his local knowledge, being part-Bengali, and his college quizzing record. I was picked to be the fourth, largely because nobody else was free. This team went on what became an epic trip—Coromandel Express took an extra day to reach Calcutta on account of a rail strike; I sampled alcohol for the first time: we were put up at the lovely Hotel Broadway where much beer was quaffed to soothe the pain caused by irritating quizzes; Naman wrote a satirical account of the proceedings which began a long tradition of inter-city sledging—but we digress.

We became college quizzing team-mates again after this trip—during my MA days–forming a team/cartel monikered BUDEL, somewhat like the exhaust from an Enfield Bullet. The acronym expanded, when required, to Bangalore University—Department of English & Other European Languages. All through college, I had been part of an Open quizzing team titled TetraCyclines[19] while Naman went with Ashwin and Raju as Metaquizziks. This team fell apart at about the time I began my MA because two of the Cyclines left for the US and the third was dying with his MBBS. I gave up and joined Metaquizziks.

Ashwin left for the States in mid-1992, leaving Metaquizziks one member short. While doing an Open quiz (my first ever) for the state Billiards Association, I noticed this stud-in-the-making from National Law School named Sandeep Sreekumar. I told Naman about this, and three days later, he had slimed Sandeep out of his Open team with college-mates Malavika Jayaraman and Joe Pookkat through a complicated deal. Sandeep and Joe would join Naman and me, while I had the choice task of telling Raju that we were dropping him. I agonised about it and eventually found a way of telling him—we wanted to found a MQ B team, and he was the best person to captain it. That phone conversation didn’t go well. I was once part of an intellectual crowd, he said, and now you want me to be part of a motley crew, before hanging up. I don’t think anybody said anything to Malavika.

Naman, Sandy, Suresh and I quizzed together in the Open circuit as Metaquizziks from 1992 to 1996. I began teaching in 1994. Naman joined the first batch of journalism trainees at the new Asian College of Journalism that year, and after stints at Times of India and TV18, left Bangalore to take up a job in Singapore with HBO Asia in 1996. The team did founder a bit, much to our surprise, after Naman’s departure. As Sandy once said, it wasn’t because of his quizzing, but ‘he was so much of a catalyst’. He would agonise over team composition, and do what he called horses for courses—essentially pick our fourth member with an eye open always for who was setting the questions. None of us cared about all that. Eventually Sandeep left on a Rhodes scholarship, Reuben left for the US, and Suresh quit quizzing. Metaquizziks survived, somehow.

While the film locates itself sometime in the ‘Eighties, much of its action is sourced from a five-year period between 1988 and 1993. There were several kinds of college quizzes—those that were held as part of cul-fests, those done by KQA, and the Rotary/Inner Wheel/Lion’s Club type events. There were quizzes on the Open circuit as well—where anybody could take part. Such usually comprised uncles, aunties, boys and girls in unpredictable combinations for several years before becoming another form of alpha-male nonsense. These too were of several kinds—the KQA ones, those held by the Bangalore chapter of the Quiz Foundation of India, and once a year, the big-ass North Star Quiz, usually conducted by a celeb quizmaster. Correct that to the Celeb Quizmaster, from now on to be known only as CQM. The film thrives on stories from out of such variety.

Uncles, aunties, boys and girls at a KQA quiz in 1990.

If you were a college quizzer then, you also went to open quizzes religiously, even if that devotion didn’t always pay off. That doesn’t happen anymore. Naman’s SJCC team was the first to win both a KQA Open Quiz and a North Star quiz. That too doesn’t happen anymore. None of us ever missed a University Selection, then a solo contest by which some three or four were picked to represent the Univ. Usually, it ended there. Nobody got in touch with you to take part in South Zoners or greater after that.

The film’s characters, despite its various disclaimers, are composites of the people named above, and then a few more. Sometimes, their names helpfully differ from their real-life inspirations by one strategic letter, but only sometimes. Most crucially, the quizzing in the film is also a composite, combining Naman’s college and Open quizzing into one beast of narrative burden.

None of this should get in the way of admitting that I have one or two quarrels with the film. But more of that later. Let’s get with what I like about the film.

***********************************

The film makes several opening moves. One features a jeans-clad butt that picks up speed after reading a stencilled poster with the legend South Zone Inter-University Quiz. We don’t immediately see who this is. In this moment we are also archly but silently inserted into the war-cry that we hear several times through the film—cover the face, fire the base. A minute later, as Naman and the boys arrive amidst paper-cups of rum, cheroots and much swagger, we see a hand in purple sleeves go up in tentative greeting, and catch a disembodied voice call out a greeting. The hand, voice and slightly iffy wardrobe come together in one package when it looks like the quiz team could get some trouble for being one member short. The girl sitting in the first row bounds up on to stage and drops into the empty seat. I’ve been preparing, she begins, and is promptly shushed into silence.

This, we find, is Ash, a girl whose braces seem to glint only to reflect how dazzled she is with Naman. Her face is forever a flower opening out in mute offering. In these opening moments she is framed in the humiliations of the gaze that the boys direct at her. Being interested and available is one disability. Being quite unlike the more pneumatic creatures who gallop in slo-mo through their imagination is her other disability.

And yet this derisory gaze is a bit of a red herring. The same camera is ambiguous about whether the crucial answer that wins them the quiz (Mills and Boon) comes from Naman, or from her. She is a trouper, and does not let being whacked aside like a rubber ball deter her from trying again. The film eventually allows us to step aside and see her as she is.

This rara avis of those benighted times we shall call the pioneer-hudugi. Who stood out not because she wore shady matching-matching outfits as she zipped past on a Kinetic, but because she was expert at ignoring pecking orders, and scaling walls, real and metaphorical, in those very outfits. I have known several, and learnt, slowly, to treasure and admire the superior fire that they carried within. Sindhu Sreenivasa Murthy plays exactly such a pioneer-hudugi to note-perfection, reaching deep to find awkwardness and a kind of raw grace. Her Ash wears the wrong clothes, sourced from the wrong regional language films, and says the wrong things (‘It’s an honour to quiz with you, Naman.’) but brings dil [20] and a sure sense of self to the small job of climbing out of the well that the disdain of the boy-talent in her world consigns her to. The film is as much about her as it is about Brahman Naman.

***********************************

Talking of boys, wherever did they find Shashank Arora? The man seems to have gone into Method mode to play Naman. The real-life feller was often one barely-compressed bundle of nervous energy, constantly drumming his fingers against his knees, and shaking his feet like he needed to keep them ready to stand up and run away, or dance, or something, while affecting great sang-froid and no great enthusiasm for anything other than his own jokes and put-downs.

Arora channels his body into the role superbly, and a trifle mischievously. He bends forward and contorts often, as if he would like to disappear into some rock concert in his head. His hands are constantly about to do things, and sometimes mime onanism while the rest of him is doing more respectable things.

His face is a thing of beauty; a vast vacantness, troubled by nothing other than an air of studious concentration while about the inappropriate, yet capable of breaking into avidity, into a kind of silent rictus hinting at inner orgies of amusement, and very rarely, into an entire Atacama spring of boyish good cheer.

While he does manage an occasionally liquid /l/, the only thing that doesn’t sit right with him is his intonation, which is simply not equal to the vocal compass of his half-Bengali, half-Palghat-Iyer progenitor.

Tanmay Dhanania’s nicely understated style works upwards from an easiness of limbs to a regular poker-face and an occasional puckering about the mouth as he shafts somebody or notices something funnay.

There’s an easy rhythm that Arora and Dhanania arrive at with each other that allows them to riff off each other at will. ‘You flick, I’ll click’ is the Jai-and-Veeru moment that the makers of Sholay should have somehow anticipated and inserted into their film.

This easy back-and-forth isn’t confined to cute little moments. It can also go into long-play. The stand-out sequence in this mode features sustained, straight-faced coruscations. They begin to run away lickety-spilt from Henry’s ladies of the night, grabbing at each other in their panic to be out of those shady galis faster and firster, transmit this trembling to some anonymous third on the way, find that they must stop amidst the searing of sheek, phal and Shivajinagar-type smells, and immediately slow down to be Brahmans transcending the beef with conversations about gerrymandering, arriving thus at the faux-deepness of the ‘Trivia—that’s all we have’ moment. The mind boggles at what might have gone into executing all this.

Sid Mallya on screen is like that unnecessarily premature burst of sunlight through the curtains that has turned so many of our video-vampire brethren to ashes. He’s not bad at all, but does no more than produce unperturbed flash. Anisa Butt, on the other hand, occupies the screen in a far more determined sort of way. Despite the briefness of the Coco-Panties role, she radiates Memsaab presence and a grim knack for playing on the social anxieties of young men. She steals these moments effortlessly from Mallya Jr.

***********************************

There is an undeniable sharpness to the way the film has been written.

Sometimes this sharpness tails off in mere smart-aleckiness, as in the case of the aquaria that bookend the film. In one more of the opening moments, a plastic diver raises a plastic something in near-onanism. We later endure a moment where the young hero mounts the aquarium to make a thoughtful donation. When the film closes, we return to an animated version of the aquarium, in which little goldfish with Naman’s beady eyes and quivering mole are making bright little stabs in every direction. Where did they come from? The Mahabharata, is my guess.

The apology he makes to Ash features a word that doesn’t quite exist—recompunctulate—prompting questions about whether this apology is real. At least one of the numbers on the soundtrack has a joke-credit directed, no doubt, at some innocent young setter of quiz questions in the future.

This sharpness turns up in sometimes in delightfully tart revenge—take, for instance, its quick portraiture of Celeb Quiz Master. Those who’ve endured the man will have no trouble recognising him.

We first come across CQM in voiceover, announcing that his name is Brian D’Costa, and that he is about to present the Cos Theta show. In that one moment, you are reminded in two little echoes[21] of the real-life inspiration. In the small overlap of his name and the show, we are offered the suggestion that he is no more than a narcissistic twit, wriggling ever forward in careful self-insertion. The Patel/Potel moment and the sudden decision to make the quiz a winner-takes-all affair are both things that actually occurred—CQM was like that if he didn’t like you. As did the expulsion of Naman Bala’s team. The film presents it as CQM’s spite in full spate, though it happened more than a year later and for somewhat different reasons[22].

Brian’s questions keep dropping in, nevertheless, and they are nothing like the stuff their real-life inspiration used to set. Perhaps we shouldn’t call them Brian’s–most of them are questions that Naman had actually asked in KQA dos. In their placing, they make for a kind of droll commentary on events in the film. Costa is played by an actor named Shataf Figar, and that is his real name. My inner Kannada-knowing beedhi nayi[23] is ululating in mystic joy at such bountiful coincidence in a normally hostile cosmos.

There are gentler moments in the film, and these work by elliptical grace. When Naman is trying to sweet-talk Rita before catching a train to Kolkata, the thing that pops out at you is a poster behind him. For a film that has Srinath, the Pranayaraja (or Romance King) of Kannada cinema, in a tight embrace with some leading lady.

Naman’s father[24] calls on the Gita while intoning a bunch of words such as tranquility, and restraint while the camera gently lights on three undies flapping in the wind after what may have a night of many excesses. Naman waddles around his house with a little tub in hand after worship making several unorthodox benedictions—in the direction of a poster of Kapil’s Devils with the Prudential Cup, blow-ups of the Tull album Thick as a Brick[25] , and the funny-symbol Led Zep album, and then his mother.

When CQM is going on about how quizzing is such an Indian thing, and about how we thirst for knowledge and suck up arcana, the camera follows Bernie as he sneaks up to the bar to order 16 whiskies on the quiz tab. These quiet bits are a different but superbly enjoyable species of sharp.

Equally sharp are the lines given to Biswa Kalyan Rath who does several pop-ins as Ilash, occasional quizzer and incorrigible teller of tall tales. In late boyhood, perfectly normal lads would suddenly turn into adventurous omnivores at least in the stories of sexual athletics they invented. Rath is memorable in his ability to evoke all of ‘em, as he calls on flashing eyes, a resolute lantern jaw, and hieroglyphs of desire produced out of a mere flailing of limbs.

***********************************

It is worth ambling around the network of invisible little ties that run from this film to a bunch of books, as also to other films, and to music.

It may make canny appeals to a constituency of boys who haven’t quite grown up even if it seems to distances itself from them in its opening declaration. Reviewers have been quick to see connections with The InBetweeners, American Pie, and Revenge of the Nerds, or talk of how burdensome the smart-aleckiness that they noticed was. To stop at these connections is to miss what the film does differently from those films, and perhaps to miss what it is truly in dialogue with. Nobody comes of age in any real sense, for starters.

When you’re young, you’re relentlessly marinated in a rhetoric of purpose and achievement. The term Uncle-speech is perhaps more accurate as a name for this rhetoric. It works by the bludgeons of harangue and homily, and soon all your lobes have been rendered into compliant strips of salami.

Naman’s father offers an ethic of hard work that resolves eventually into priceless sentences such as ‘a vertical fibre orientation that allows deeper latex penetration’. Naina’s father, in his brief appearance, offers a more thuggish version of the same thing. Even Bernie, who seems like the antithesis to all the uncles in the film, is no more than an exponent of the art-form of living off a practised spiel.

These adult presences organise a sense of the bland exhaustion that can come from living inside the speech of others—be it success or political correctness. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, through its attack on phoniness offers a simple-minded engagement with the irritations of uncle-speech. Brahman Naman’s target is the same even though its ambitions are different from the Salinger novel. The work that it is closer to in spirit is Tibor Fischer’s Under the Frog. And several others from closer home.

A straight line can be drawn from the film, in its distance from prescribed aspiration, its avoidance of easy resolutions, and its capacity for irony to Upamanyu Chatterjee’s retelling of the stranger-in-a-strange-land idea in English, August[26]. That book was read and re-read in our time, and little bits became part of our conversation. I remember the way in which we fell upon the film[27] when it played at Lido in 1996—a little bit like we’d been given access to a great big bottle full of fresh air.

Similar geometric connections can be made with the narrative ambition in Anurag Mathur’s The Inscrutable Americans. This too is a story of rampant desire shaped by repression set inside a fictionally uncharted territory—studying abroad in the case of Mathur’s novel, and surviving college in this film.

One of the characters of our adolescence was the P. D’Souza who appears on an address in the film. His randiness was legendary—and usually involved near-misses with lynching as a result of what he would get up to while on the terrace. When this wasn’t happening, he was usually dodging terrible humiliation in the family for doing completely non-randy things that were anyway read as going in the opposite direction. His adventures have contributed in some small way to the film. At some point in the 1990s, all of us would come across Richard Crasta’s Revised Kama Sutra, and marvel at how life, in the form of this D’Souza had somehow upstaged art.

Another book from those times that the film seems to point at is Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia. The somewhat becalmed lives of its characters, and their desire to be elsewhere are one point of correspondence. Creamy and his circle, from the book, expand on desire in more ways than one, and that is the other point of correspondence. Kureishi’s book is set in the 1970s, in an England on the verge of becoming Thatcherland, and that may allow us to open another line of thought in a little while.

The narrative ambition of these works, that of locating and reporting the undocumented, provides this film its minimal soul. The other thing that it draws from them is a fund of irreverence.

Apart from these works, there’s one writer whom most people think of today as either cutely stylish or simply too dated to matter. As evidence, I offer the simple fact that no writer talking about the film has noticed his presence in the film. He did confine himself to a class, and acknowledged sex only in the most oblique of ways, and was generally genteel by today’s standards, but brought to his writing an eye for the ridiculous and a genuwyne talent for mixing registers and voices. Brahman Naman’s biggest debt is to the original master of irreverence, Pelham Grenville Wodehouse.

What comment is the film making through its visitations of the past on our present? The present is, alas, a world where uncle-speech goes unchallenged. Naman’s gift for combining paraphilia with verbal irreverence completes the trajectory that Roland Barthes once set for the term jouissance. Perhaps such jouissance is escape, or remedy.

I’m giggling while I type this paragraph. Because the real Naman’s sepulchral voice is intoning the magic formula Rubber On is the mattress of copulation for the entire population on my computer’s speakers even as some louder fornicator is yelling the words you are tigaaars, not sheeps into a mike at school kids who’re sitting like animals trussed up for the Tannery Road slaughterhouse. They’re in school uniform, and are attending a yoga camp on a Sunday morning in the playground opposite. This, he says with a vocal trill that sets the mikes keening, is the way Vivekananda made some Maharajah X understand some lofty principle, and that is why he is a great man. That, sirs, is the present moment in a nutshell.In our time, even our buttocks wouldn’t have looked at the school grounds on a Sunday morning. And anyone making such a speech would have perished in three minutes, in a cacophony of animal and bird call-and-response.

The film’s soundtrack is a separate joy, and one that possibly deserves another writer altogether. I shall confine myself to emphatically liking the way Locomotive Breath becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy across the film, as also how Alabama Song is pitted against it as an anthem-cum-SoP.

Apart from what happens on the soundtrack, a tissue of references is summoned up from the British-Beat-inflected imagination inside which these characters live. Music from this era is the footnote to every trivial moment. The almost -working-class white boys who mined Black musical traditions such as Blues and R&B to become the Beatles, and Herman’s Hermits, and Foreigner were drawing on a foreign fund of irreverent resistance for warfare at home. The film draws quite deep from yet another source for the same reasons—the sketch-driven stylings seen in Monty Python and Blackadder, and the general black humour of Peter Jackson’s Bad Taste.

***********************************

How original is it to borrow? How do we understand these borrowings?

If we begin with the title of the film, we see that its characters are Brahmin, and yet uncomfortable and at odds with this in ways that are silent. There is a heterodox (shall we say Sudra?) impureness that they are constantly compelled towards. Much of what they do is a hybrid mixing for which we shall fall back here on a term much beloved of theory mavens—bricolage. The use, in other words of something for purposes other than what it was intended for.

Naman is leader of his pack in that his gift for being a bricoleur is apparently endless. Quizzing becomes an unorthodox way of knowing. The simple adolescent act of onanism must extend to a remaking of the domestic–into a refashioning of fridges, and aquaria into stand-in yonis and into inventing a hands-free mode much before mobile phones.

The clean if convoluted language of Wodehouse’s irresponsible young men (The Mating Game, and other Bertie Wooster stories, where the real Naman may have first come across a beaker full of the warm South, or Eggs, Beans and Crumpets where he might have first chanced upon a love like a red, red rose) is compelled into cohabiting with scatology and sundry Anglo-Saxon to constitute a dialect of irreverence whose effects are very much like walking into the path of a machine that sends down tennis balls in high-speed serves.

This bricolage is a talent for reaching deep into a compendium of borrowings to break and make use of them in unexpected combinations. The nonstop conversational joshing, the scarcely hidden jouissance of the film, comes then from this creative act of putting together unexpected combinations from what you have borrowed.

What is all this bricolage in aid of? Samanth, in an otherwise excellent response to the film, has a deep aka poopy-bum-banana moment when he looks at the ‘we have only trivia’ bit after they run away from Henry and his night-queen. This is, he says, a cri de coeur. A cri de bulla is more likely. And I mean the Latin bulla, a sign of authority and ownership, not the delightfully evocative South Indian word for other things.

The film borrows from our adolescence in a time that was defined by events we may describe as historic. The Soviet Union fell, the Iron Curtain evaporated, India experienced two versions of liberalisation, Masjid and Mandal became household words. And yet, the film is curiously silent about all this.

Apart from snatches of Brahmin-supremacism, little in the film seems connected to those tumultuous times. To understand how Brahman Naman manages to chronicle something significant, we need to travel only as far as the British theorist Raymond Williams’s ideas. While talking about how the common sense of a time may be powerful, he points out that it can never be total. Rebellion may occur, or not, but much before anything so melodramatic, there is always an inner kerfuffle in response to this common sense from which new formations of thought emerge—a process that he describes as ‘a structure of feeling’. Such a structure can be inhabited without overt articulation or anything more than an inchoate awareness of discomfort or difference.

Somewhat like the zone of discomfort that the film offers us. An in-between period where several kinds of rhetoric from the past are still around and newer competitors are trying to replace those. The characters are seen tiring of some kinds, trying out others, and sometimes manage a kind of undecidedness. This is a little bit like the landscape that Kureishi’s novel offers, even though his characters seem to inhabit a world that offers more by way of experience. Q’s film allows us to see the interstices of such a time, and how they could become home. Quizzing is one such home. The English language is another.

If we may rephrase the questions we began with: what is original? And what is duplicate? This anxiety frames at least one part of the Ronnie-Naman face-off in the film. Kai Friese likes to call the times that we lived through the Import Substitution Era—one where some things were verboten because of their origins or their ideologies, but could be replaced by local imitations.

These replacements have happened to Playboy, to English and quizzing, and what the film offers us are these artefacts as if they are Thums Up rather than Coke.

***********************************

I have some quarrels with the film. Chief among them is how the characters are denied any interiority. Some of the things the film manages to do might have been amplified by such attention. Instead, they are constantly in each other’s pockets, or expelling body fluids in some form or the other.

A bigger problem is the film’s diffidence when it comes to staying with quizzing as a sport. We are told that they are quizzers, but all we see are little photo-finishes of them winning or losing quizzes. Quizzers often doubled up as quizmasters, but we see very little of that. The prepping, the bitching and the post-mortems find no place on screen. The college and open circuits overlapped in those days, but were nevertheless quite different from each other. The film compresses them, and that is a lost opportunity.

Author, back to camera. KQA 5th Anniversary Open Quiz 1988. Team Venceremos: Bharat Patil, Shaktish Acharya and Anjan Shah

And then there are those young women quizzers from Chennai who are foisted on to the storyline. No such thing ever happened—which is alright. The stuff that actually happened was far funnier.

When we were stuck in Bhadrak, Orissa for 8 hours, Naman spotted what he described as a quintessential Iyer beauty in the window of another stuck train, and so he went away and sat on a bench opposite and looked at her for all of those hours, and fell more and more deeply in love with her. That train left in the evening and he returned to our compartment looking like a punctured tyre. When I began teasing him, he actually turned away and glowered out of the window.

I then went for a walk and came back with roti-sabzi from a cart outside the station. On the way back, I heard somebody at the station-master’s office mention that the Cochin train was stuck at Balasore. Since this was the one with the lady, I told him what I had heard. He did not deign to respond. At midnight, I heard somebody say Balasore, and then I heard him running up the platform, his hawais slapping on the surface like heartbeat on the soundtrack of a Bhojpuri film. He came back and cursed me roundly because that train had already left.

Another time, at some party in a Frazer Town flat, some fan-girl tried to say vaguely romantic things to Naman and then to Sandy inside about ten minutes. Both of them responded in the same way. They jumped from the first-floor balcony into the shrubbery below to avoid having to deal with her.

Enough narrative mojo could have been found in details like these, but those chances are never taken.. Instead we must suffer these bakwas fictional Madras women who know that Jim Gordon co-wrote Layla, who Graham McKenzie was and what the last song on the White Album is titled.

This dabba romantic interest does nothing for the film. It sounds like some dingbat attempt at raising the sketch-after-sketch structure into some kind of story arc. It might have been a better idea to risk staying with the slower possibilities of quizzing, and the big deal that cul-fests were, in colleges, in a much smaller city, and the vague aspirations beyond all these. And to have allowed it to become the longer, more substantial albeit riskier film that it could have been. In this form, despite the art that has gone into comeuppances and coups-de-grace, it’s a bit of a cop-out.

***********************************

So Bernie gets more action than Naman does, Ash dumps him for somebody scrawnier, and Rita refuses to be his meter-maid. Is no cinematic redemption possible for Naman Bala? The film offers him none. Unless you look carefully.

The real-life Naman had to do a B.Com. Not because he particularly wanted to, but because he came from a business family and that was the done thing. He must have died of boredom, and found more to do outside the classroom—the film offers enough evidence of this if you contrast the classroom scenes to the canteen and standing around scenes. When I applied for MA English at the Univ, he applied along with me, and chattered away about what a relief it was to apply for something he might actually enjoy. They rejected him because he had only a 54% aggregate in General English[28]. He then spent two years running a Cuticura talcum powder unit in Ramamurthi Nagar, taking breaks only eat lunch or to drive up to nearby Banaswadi to plot quizzing mayhem with self.

In 1994, Indian Express began a journalism school[29], and Naman abandoned talcum to join this school. He began writing like a man possessed—he had always been a solid reader and was the only person I knew who had read nearly every Indian English writer then in print. He then did a legendary internship at ToI; where he wrote 30 pieces of a good length on film and music in 28 days. They gave him a job, and the rest of that history we have already gone over.

Naman Bala himself, if you notice, knows his Yeats well enough to bung his poem about drinking into a love-letter, even if he calls him the immortal Butler, and that might be some hope. The other thing is that he’s constantly seen writing, and it can’t all be quiz fundas. This Naman’s real moment is when you see him plunder from his father’s breakfast monologue and turn it into something else altogether featuring a television screen, Ajay and him. A kind of Bildungsroman plays peekaboo with us briefly and never reappears.

***********************************

I had heard about the film, and watched the trailer. I had read about it premiering in Sundance. Prior to all this, I had a sit-down with the AD and some the cast who wanted a general backgrounder on quizzing in the city. I was thus fairly curious about the film. And that was when theory maven and Bangalore hotshot Lawrence Liang Whatsapped me thus:

[5:04pm, 21/02/2016] Liang: Wanted to ask you if you wanted to watch bhraman naman, but what a ****ing disaster, one of the worst films I have seen

[5:19 pm. 21/02/2016]Arul Mani: Hahahahaha

[5:23pm, 21/02/2016] Liang: F***, he is still seventeen, also reduces his and everyone else’s experience of quizzing into an endless orgy of horniness and bad humor

[6:20pm, 21/02/2016] Arul Mani: Tweet to him.

Silence.

Liang’s irritation was hard to fathom given the fact that his career as Bangalore superstar had been a lot like Naman’s. Horniness and bad humour have been part of his life for longer than I can remember, and they are hardly hanging crimes, or serious artistic failures.

They are indeed the first thing I noticed about the film. I didn’t have an instant opinion to send out because I don’t have Liang’s speed-reading talents, and because, as I said earlier, I had the feeling that I had missed something. Each time I returned to the film, I noticed something quieter happening, and ended up watching it more times than I had planned.

There’s a moment in the film that’s emblematic of all this. Ramu, for instance, doesn’t get to be very much more than butt of everybody’s cow jokes. But he too has his moment. They are standing around the canteen while Ilash is jawing about some new conquest. The bell rings. Ramu leaves for class. Naman decides to go to class, and in reply to Ilash’s amazed question about this rare event we hear that Anisa Butt’s character is about to flash the world. Ajay starts singing the words to What is the Colour of the Colour TV? and everybody makes gross noises. When I thought to look for Ramu, I saw that he hadn’t left. He was standing far away from his friends, but air-guitar-ing with his crutch, his face contorted in inexplicable bliss.

This energetic mischief on the peripheries is what I liked most about the film.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dk7Ba6oow8U

[1] Or indeed two assassinations, if you prefer Aravind Adiga’s name for that time

[2] Even colleges would allow students to smoke, as long as it was confined to the canteen.

[3] They had ‘under-the-table’ service. If you tipped the waiter, he would get you your plonk. You had to place the bottle under your table, though not your glass. Even an overtly Malabari Muslim joint such the old Empire, on Residency Road, or the Chinese restaurant Silver Plate, would allow this

[4] Quizboy-tragic term for normal forgetfulness.

[5] ‘Little water’.

[6] Friendship,in Russki. Also means union(!).

[7] The scriptwriter. Pronounced nɑːmʌn, a shortening of his given name Sahasranaman—literally ‘him of the thousand names’. The opening credits have a jokey allusion; when his name appears on screen in one of the film’s several splats, a cartoon Naman lies on a mattress that turns into a thousand boobies.

[8] Maulana Azad

[9] Bangalore’s tabloid weekly of the 1980s begun by Abraham and Gita Tharakan. C.K.Meena, Allen Mendonca and several others began their careers here.

[10] Shyam Sundar reviewed television and wrote a quiz column for the Tab. He is now Mass Communications professor at Penn State. In 2003, I wrote to him asking him to contribute to KQA’s 20th Anniversary celebrations and laid the blame for my getting into quizzing on his tie-breaker. He didn’t know me from Adam, but sent money anyway.

[11] A sadly multicultural combination of the Karna Complex (knowledge deserts you at crucial moments) and the Alexander Pope complex (A little learning, drink deep, etc.)

[12] Aka Amladi, usually spelt Almadi on most quiz certificates.

[13] Short for Rajsekar.

[14] One of us would set 50 questions, and the others would suffer them. The idea of written rounds, now a staple in Bangalore quizzing, began here.

[15] “I came, I saw, I conquered”. From Julius Caesar’s letter to his friend Amantius following the Battle of Zela in 50 B.C. There’s a story behind this motto, but let it be.

[16] Now known as Kiran Natarajan. One of the people behind the mammoth FaceBook group Bangalore: Photos from a bygone age. Doesn’t quiz any more.

[17] Also doesn’t quiz any more.

[18] Or Hernie as he came to be yclept after the Calcutta trip, was perhaps the first openly rightwing quizzer I’d ever met. He had taught English, and worked for sometime on All India Radio while also being a swayamsevak. He wrote a book titled Hindu Destiny in Nostradamus in 1986, which proclaimed, among other things that Hinduism would become ‘the rose of the world’ in 1996. On the trip he regaled us with witticism after witticism, while we gagged silently. The sultan among these was one about the railway station Bitragunta. Since Gunta means woman in Telugu, the station, he said, must have taken its name from some woman who grew embittered here.

[19] A slightly MBBS kinda joke, because we were four in number. Thought up by Ramaprasad, then in Bangalore Medical College, for the team he formed with Gopakumar, P. Swaminathan and self after the sad demise of Ganesh Nayak.

[20] Hort.

[21] Of his name, and the real-life quiz show that he helmed.

[22] At the 1993 edition of an all-India Open Quiz, Metaquizziks was expelled for not drawing their lot in time. Several teams were locked in an unending tiebreaker for the last place, and CQM had lost count of how many questions he had asked, and how many teams he had let into the finals. When he realised his error, he turned it to advantage rather than acknowledge it, and disqualified MQ.

[23] Street dog.

[24] This merits a footnote. Ashok Mandanna, who plays Naman Bala’s father, was the answer to the first ever video question played at an MQ meeting. Naman played a clip from Passage to India, where Mandanna plays an Indian servant, and asked us to identify him.

[25] Easily recognisable, even though it’s at a corner of Naman’s room. Because it is the front page of a newspaper—the St. Cleve Chronicle and Linwell Advertiser—with Gerard ‘Little Milton’ Bostock, the protagonist of the album, figuring among the headlines.

[26] Naman used to be very kicked by one cruel description in the book—some character X was so fida over America that he was likely to go and get AIDS because they had it in America.

[27] Directed by Dev Benegal. One of the great semi-lost films of our time.

[28] Don’t ask. Some antiquated BU rule.

[29] The original Asian College of Journalism.

Arul Mani

Latest posts by Arul Mani (see all)

- Twelve ways of looking at a film and seeing something else, or nothing at all - 29th April 2020

- Three tight whacks and the book of Avarna revelations in Ee Ma Yau - 20th June 2018

- If you’re Socio of your opinions, then read this - 24th October 2017

Rajsekar 15th August 2016

Correction Mr Mani ….I was not “dropped” as you put it – there was a lot of internal politicking during this time.Anyways, fact remains that i started working after 1992…leaving me with no time for quizzing anymore.

The Open Dosa Team 16th August 2016

What ra Raju. If you insist. The conversation happened though.

rajsekarvj 20th August 2016

Thanks bud….long time….lets catch up one of these weekends

Patti Helena 10th January 2022

Hello

YOU NEED QUALITY VISITORS FOR YOUR: opendosa.in ?

We Provide Website Traffic 100% safe for your site, from Search Engines or Social Media Sites from any country you want.

With this traffic, you can boost ranking in SERP, SEO, profit from CPM

CLAIM YOUR 24 HOURS FREE TEST HERE=> http://jeffreysbgl29629.bloggerbags.com/8099252/get-quality-visitors-for-your-site

Thanks, Patti Helena

Charity Foutch 5th April 2022

You are looking for Free Backlinks then you came to the right place.

We offering you a free trial to try out our link-building service.

This can be used to link out to your website, inner page, google map, video, to any link you want to help power up and get more relevance too.

We want to prove to you that our backlinks work and so we’re willing to prove it to you risk-free.

Please create an account and then watch the video and submit your order details and let us help you get found online.

FREE TEST HERE: https://zeep.ly/McQvo?=2329

Josef Burt 5th April 2022

YOU NEED REAL VISITORS FOR: opendosa.in ?

We Provide 100% Real Visitors To Your Website.

With this traffic, you can boost ranking in SERP, SEO, profit from CPM…

CLAIM YOUR 24 HOURS FREE TEST HERE=> https://www.fiverr.com/share/8AaDqo