The croaking of frogs is first and foremost coastal, and only then usual. Mangalore coils and uncoils itself inside a mountain made of red mud. It is a strange city where slopes suddenly emerge on otherwise calm, yet accident -prone roads – as if angry with the skies, and angrier with you.

Houses appear like broken teeth carved into paan- soaked red mountain mouths. Like little board game homes, they sit peacefully – even if they look like they are all going to fall one by one.

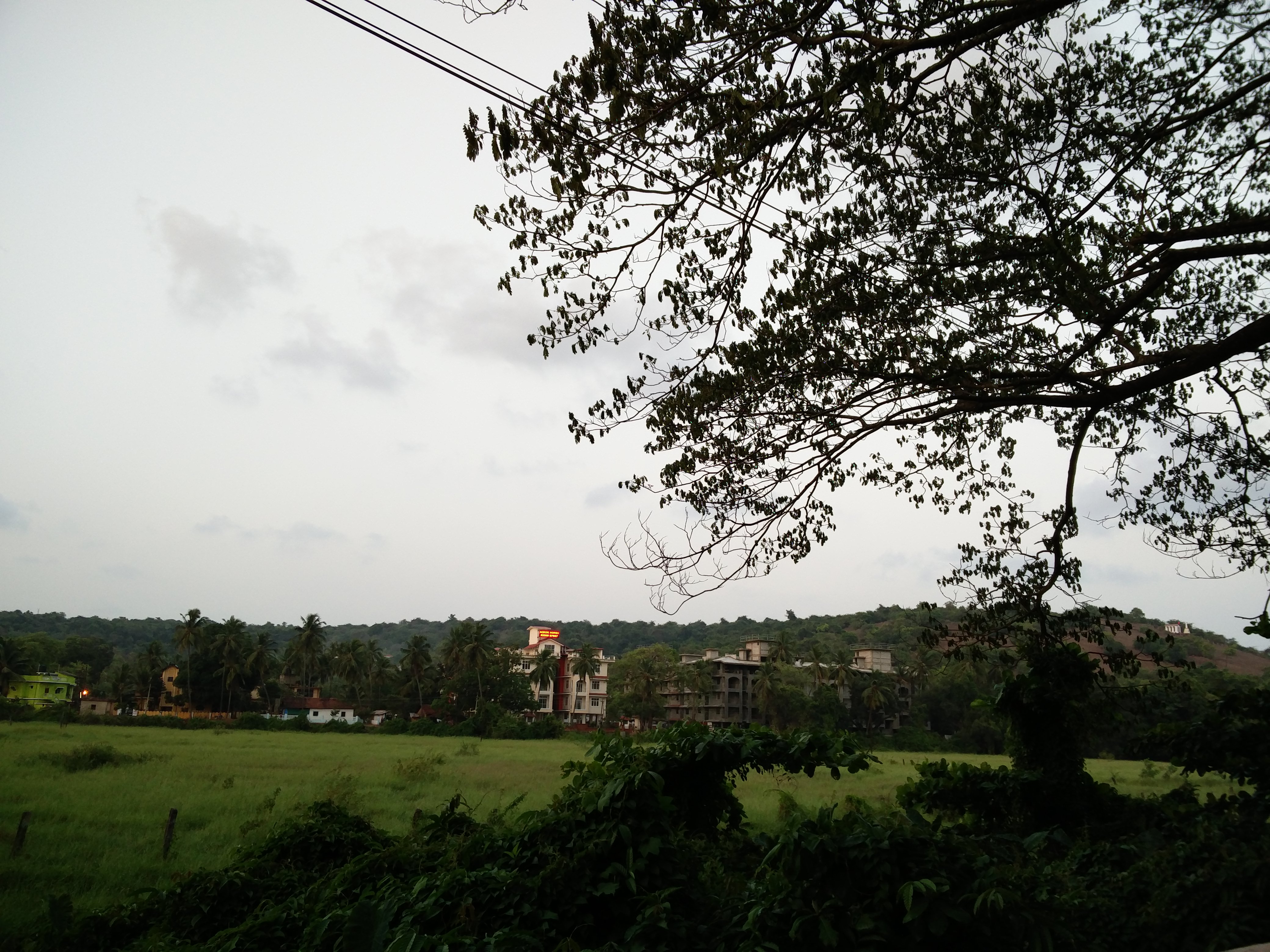

The frogs come in the evenings and line themselves neatly by the fields next to the home I grew up in. And here they take methodical turns to begin croaking.

Sometimes the Frog with the abnormally large brown eyes goes to sleep and forgets to croak but he must wait his turn to croak again. After the Croaking of Frogs in Public law (implemented in ’46) two frogs never croak at once. It brings bad luck.

That home is the stuff of many childhoods. And mine began and ended here. Many years later, as I walked hesitatingly towards this home which was rented out to another family, I was not surprised to find that the gate was still drawn out. Even back then, when we came here to spend the summer – the gates would never close. Not as a rule, but just.

The solid cement on the ground had cracks here and there and had resolved itself into small mounds of its own fragments–as if someone had lifted the ground off the earth, broken it and placed it back again very carefully. The Tulsi katta was still there as was the ghost of the plant, while all around it, a forest was silently assembling.

***

My father often recalled someone who said that having a bath in Mangalore could be a very confusing ordeal. While you poured water on your front, your back would be wet too -with sweat.

But because we were with cousins – and because these were faces that we saw only once a year — we didn’t care for the searing heat of summer that sent drops of perspiration rolling down our backs every time we laughed, our bodies breaking into wobbling jellies.

We rarely stepped out of the house because there was always so much to do at home – but when we did, we went to Pabbas and Ideal where ice creams were gobbled down like Pani Puri. Hangyo! was the first ice cream joint to serve softies. It took me a while to figure out that in Konkani, ang yo – means – come here.

While we spent the slow afternoons like houseflies – noisily soaking in the dalitoy smell from the kitchen, the TV would resolutely be on to MTV where sometimes Urmila and Fardeen’s bodies appeared and disappeared behind blood red sheets and Falguni Pathak’s warm honey voice somersaulted in blue suits.

The house baked in a warm dalitoy smell in the afternoons and the sizzling orange of tap–tapi in the mornings. Tap-tapi is what we called peas curry. When the peas began to boil in the watery orange curry, their skins would peel and float, making the bubbling tap-tapi noise.

TVs had a volume of their own here and this was the most liberating thing about the house. It was always blaring loud no matter who was around. Back home in Bangalore, every time I sensed my father’s mood swings, I wished all the TV volumes in the world would mute. But in Mangalore, rules bent themselves so neatly that we sat on them and made paper boats.

The last room had treasures of my favourite kind. I say last and not corner because the thin corridor that stretched beyond the hall had rooms appearing on either side like compartments in a train bogey.

Gunny bags of tea powder were piled atop each other in this dusty, red -oxide tongued room. Sometimes I climbed on top of these rags and lay there, on my back – thinking about how much I hated going back to Bangalore. The opening themes of Shanthi and Swabhimaan become my rebellion music and I spent the rest of the afternoon plotting my escape from Bangalore.

The backyard had a brick walled bathroom where a huge aluminium vessel was placed for water to boil. My sisters and I came here in the evenings to bathe. A yellow bulb hung loosely in a corner and all the steam from the boiling water rose up, making the yellow dance in in its glaze.

When the rains came, the clothes never lost the naphthalene smell, not even after being washed. Faraway frogs lined up closer and everything would feel wet because of this, even after the rains had stopped.

Mangalore

We were forbidden from whistling in the evenings. It was believed that snakes came looking for the whistler and if the main doors were shut, they’d attach themselves to the circle designs on the door.

Somehow it stuck in my head that if there are frogs around then there are bound to be snakes. Years later, even though I’m delighted to find audios of croaking frogs and night sounds, I don’t find the courage to listen to them without earphones and when I do, I keep looking back – half expecting to find several snakes slithering on the floor.

In the dead of the night, if you woke to drink water, the frogs would have all attained a band-like harmony.

Their croaking would’ve become more or less uniform and even the last frog, with its abnormally large brown eyes would follow suit – no one missing a turn.

***

Goa

I never learnt Goa’s sounds the first few times. When I went there with my parents, I only heard the slow, rhythmic beating from the sound of a discotheque in the basement of our hotel.

Then I heard the waves coming and going in the morning. Even so, the sounds of my parents’ approaching footsteps were the loudest. I’d hurry to turn off the TV.

I heard the frogs on my second solo visit to Goa. They seemed to be standing closer to me than the ones in Mangalore. Their croaks were stronger, clearer, and needier– like the vision of newly divorced people. In the balcony of the homestay that I rented, I’d sit and listen to their symphony every morning with a mug of chai.

And when the resort next door erupted into a chain of Chennai Express songs, the frogs dispersed –hopping merrily from stone to stone. They promised to come back in the night and they did — every one of them.

In the afternoons, Goa and Mangalore have the same slumberworthy capacities. The heat becomes duller, settling on the eyelids — making it heavy with sleep. And if there are trees around, the occasional rustle of the wind sends the birds into disarrayed flapping of wings, causing many hypnic jerks.

The short dreams are always about birds – flapping eyelashes instead of wings. And, of aeroplanes that fly dangerously close to huts.

In the cab, on my way to Bhatti Village – which is the only place I want to die in – with pork vindassol, pao, and fenny – the crickets chirp in and out of the warm window air.

Nerul

In Nerul the only vacant bits of land oscillate between tall churches and wide trees – and the frogs here sing delightful rhapsodies to my smiling stomach. The frogs and I are happy here and beat with the jhilmil of a heart set on love.

***

There are no frogs in Bangalore. And if there are any — in Basavangudi, they are overpowered by maniacal dogs who bark all night and slow cows who sit and chew all day.

Cows in Goa

Latest posts by Vijeta Kumar (see all)

- It was supposed to be Pascal’s Triangle but you two came - 2nd December 2024

- A review of Mother steals a bicycle and other stories - 17th November 2018

- What happened when Bengaluru’s working class women had a #MeToo meeting? - 7th November 2018

Karine 29th October 2021

You can certainly see your enthusiasm in the article you write.

The arena hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to say how they believe.

At all times go after your heart.