Three Singer sewing machines make squeaking and tak-tak noise in the stifling heat. The clacking of letters from Thatha’s typewriter can be heard, not enough to be part of this beautiful cacophony, but it lingers – making itself known. Listen harder. There’s the sound of a boy in a checked shirt flinging a spin ball and soon follows, the groan of another boy who got clean bowled.

Mannarguddi, apart from its kovils (temples), cows and kambli poochis, was the large stone home filled with dust and chattering. Amma, perima and paati sit in this one specific room that smells like baby power and musty cloth; they weave stories after stories, sharp needles moving as fast as their pink mouths.

As I remember it, Perima is making a pavadai for the next door neighbour’s child whom she met yesterday for the first time. Amma is knitting what looks like a misshapen scarf, an odd jumble of colours while Paati stiches two blouse pieces – orange and blue, for her daughters. When Amma returns to Mannarguddi she wears cotton saris and discards her Bangalore chudidars and kurtis. It is in this room I notice that all three of them have the same dimples but different ways of laughing.

Fascinated, I watch shadows move around while picking up pieces of cloth and fetching different colour threads when any one of the women bark out loud orders. They talk about a dog they had, Assei, who is imagined to be fully tayri (curd) colour with kutty brown spots.

They talk about all the mamas and mamis in the house who never let them leave the dining room till they ate everything on their plate. Someone brings up the topic of a mama who died recently and a sort of almost-silence falls, but the laughter returns soon enough. Papa often jokes that they sit and talk shit about their husbands, but I grimace because husbands hardly matter in this bubble.

They mostly talk about stitching projects. The conversation always strays back to what they’ve recently sewn and the biggest debate is between what is the most efficient-cross stich or running stich, crochet or knitting.

Later in college, an English external examiner tells me about glassy-eyed women during wars who listen to radios, and sip on cold tea. I find that in times of war the three women I know, sit with Singer sewing machines and drink three cups of chai, two cups of coffee and force all the children to drink three cups of Horlicks.

Sipping her chai, Paati picks up a piece of khadi cloth on which she has done an embroidery of The Afghan girl. Everything but the eyes have been embroidered. Paati holds up green thread and her needle thoughtfully. She doesn’t talk about how daunting it is to sew the eyes but instead, talks about Kumudini- a Gandhi-supporting ancestor of ours while caressing the khadi.

Ay, you know she made this one pamphlet where she designed a skirt and top that looks like a nine yard silk podavai?

Ama wa?

Ayo seriously. And she called it ‘Nine Yards made easy.’

Amma and Perima cannot believe it and they start imagining the expressions of absolutely shocked TamBram relatives. Later, we turn the house upside-down (as Amma puts it) trying to find the pamphlet. When we finally give up, an agreement has been made.

Uncomfortable nine yards should not exist.

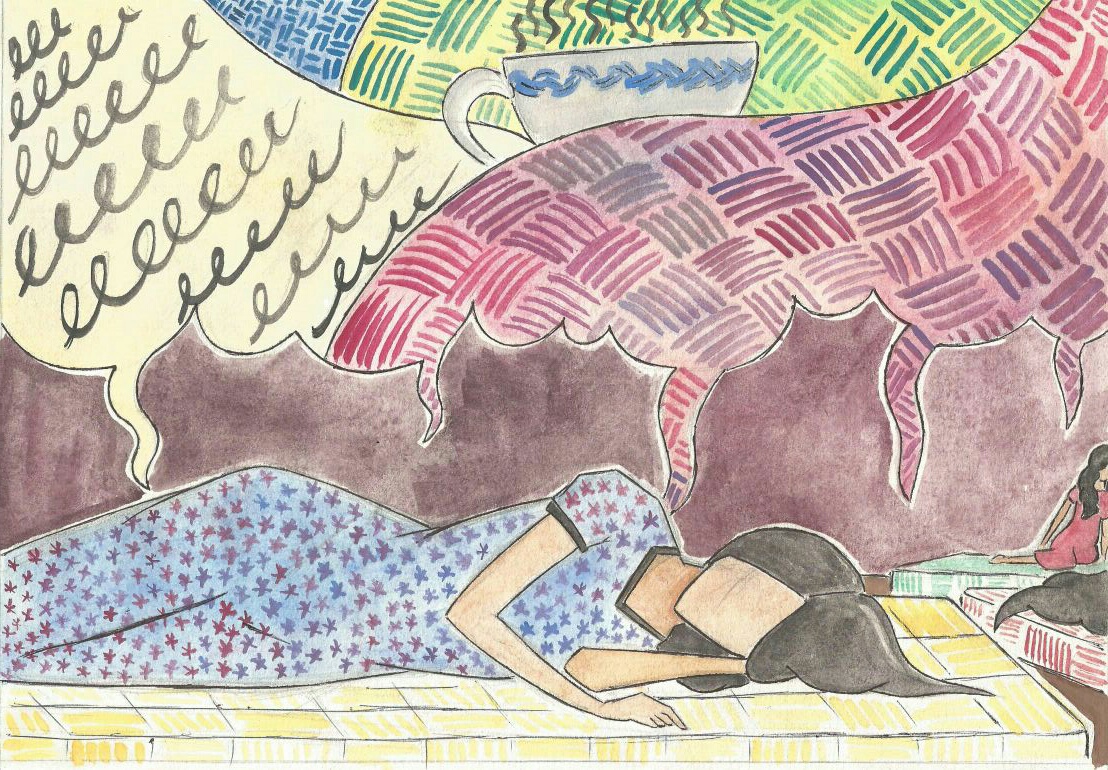

Night falls and the sound of sewing ceases. Instead of chatters and loud exclaims — cool and satiny whispers ripple like the bottoms of flowery nightdresses in front of an air cooler. We all sleep in the hall laying many thick mattresses onto the cool stone floor.

I watch the bright orange dot travelling down the mosquito coil as scandalous stories begin to surface. Perima finally tells Amma what was in the letter Peripa gave her during their engagement. Amma giggles and her unsaid words mingle with them. And I giggle with her imagining a young Peripa who had a long curly Quick Gun Murugan moustache.

Paati tells the story of how her brother, Ram Thatha, married the most beautiful woman in the world. She was German and her name was Gertie. She later shows us the beautiful cursive handwriting in Gertie’s letters and tells us in detail about the more beautiful wedding.

With stars in her eyes, she recalls the moment when Gertie walked into her childhood home in Calcutta, and the jaw drop of Paati’s mother.

Illustration by Donna Eva

I play my part and tell them about a rose pillow I like very much, to be part of this conversation.

I realise that these stories seem to spill out when the lights are off and there is no eye contact, just the swirl of smoke-like voices hovering in the air and the feel of rough tickles from long plaited hair.

When I no longer visit Mannarguddi, I realise that these sounds and chatters travel like the people who create them. Be it Madras, Madurai or Bangalore — the same routine follows and these sounds somehow very suspiciously, but very magically, make a house a home.

When Amma, Perima and Paati start conversations on the family WhatsApp group, I can almost hear the tell-tale sounds of sewing.

Archita Raghu

Latest posts by Archita Raghu (see all)

- Chalo - 28th January 2019

- A Koramangala that Thoongamoonji-ed a long time ago - 23rd August 2018

- If Courage was still my Friend he’d call me Cowardly - 17th March 2018

Philip Victor 23rd August 2017

Oh my god. I loved it Archita. Good job. I loved the painting as well. Nicely written