My relationship with desire is one of secrecy. I discovered things I knew nothing about long before anyone I know opened up to me. This made me wonder why no spaces existed to talk about something as rudimentary and human as pleasure. This made me wonder how this system of chuppi had come about, where people kept their desires hidden under their belly. Did ancient India live lives of pleasure behind closed doors, too? If not, what changed?

Vinit Vyas’s workshop at the Love, Sex, Data conference organised by Agents of Ishq and The YP foundation in October 2021 was a great insight into many ancient erotic paintings that mirror our desires. The desires existed not only in secrecy, or implied behaviour but also in the ‘public eye.’ Why? For there is a pleasure to be derived in so many ways! Of course, the paintings Vinit brought to us thrived on the undeclared. Many paintings did not know who painted them. There was no manuscript in many other paintings. However, they were teeming with emotions. It was impossible not to try and look at them and wonder if they’d come to life in front of our eyes.

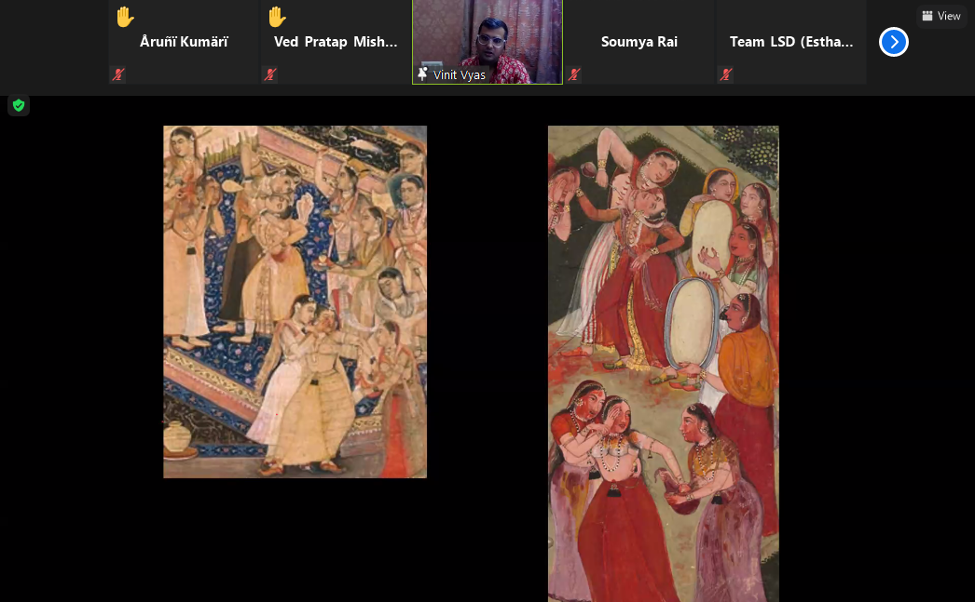

The spaces between secrecy and culture began closing as Vinit showcased paintings depicting the festival of Holi. Growing up, I had often found myself looking forward to the chaos of colours that Holi brought, and the water and the banter and the music and the intimacy. The intimacy, both chaste and otherwise, sat inside of me without knowing how to entirely emerge. The innate ardor of Holi displayed in the paintings made my secrecies feel seen. The stolen moments of connection in the banter of rubbing gulaal made me realise that Holi was, indeed, a festival of pleasure, of connection, of Dosti. The depiction of women holding each other while applying colours made me ache for a safe space for expression away from prying eyes. It made me ache for something amiss from my growing years.

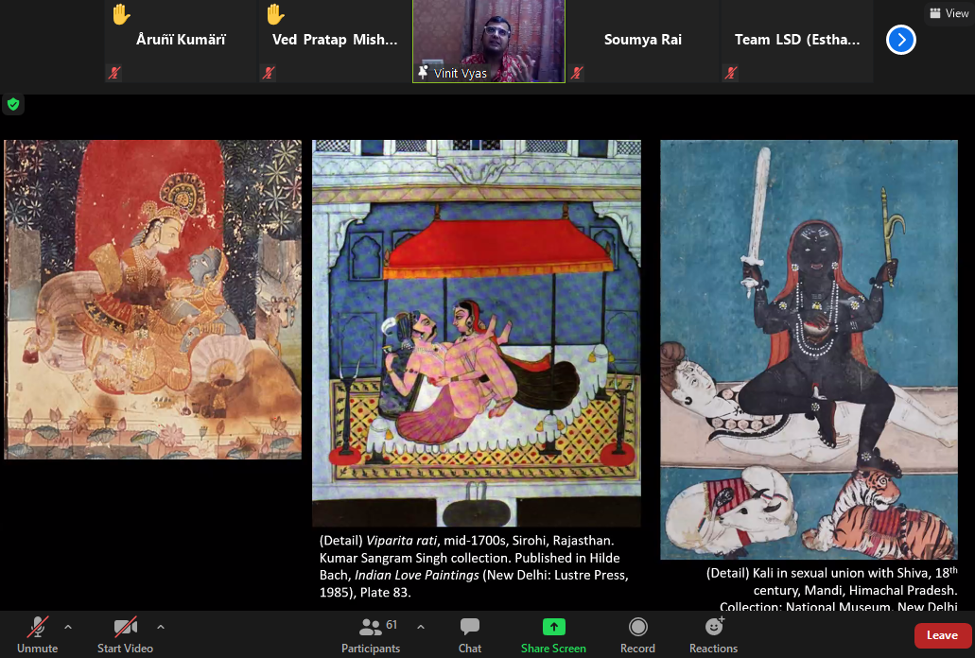

The paintings also depicted cross-dressing, genderfluidity, and many more things Indians still struggle to gain a public congress for. One particular painting depicted different scenes of banter between Radha and Krishna. In The Reversal of Roles, Radha urges Krishna to wear her ornaments, and for him to let her adorn his ornaments. Many other paintings saw lovers disguised as women, making the idea of impersonation liberating centuries ago. There were many compositions that depicted genderfluidity. Even if the male gaze was arguably prominent in these paintings at first glance, they at least opened a door for dialogues of agency.

The various puns depicted in some other paintings seemed like the blend of humour and pleasure that today’s entertainment should take notes from. It was also a rebellion of sorts, a loosening of the tight grip of patriarchy that has always existed in matters of pleasure.

The queerness in me, the very thing that pains me to define but exists within me boundlessly, came alive in the paintings. It came alive in the portrait of two men lovingly “adjusting turbans” while gazing into each other’s eyes. It came alive in the portrait of two women calling each other’s breasts carded cotton. One was of stolen queer moments that I had aplenty, the other, of acceptance. I still ached for that.

Soumya Rai

Latest posts by Soumya Rai (see all)

- The spaces between then and now: Vinit Vyas on Tik-tok and Ancient Art - 30th December 2021

Nupur 13th January 2022

wow <3