He never returns the ball if it enters his compound. The shot was hit by Dheeraj. The rule of the mohalla was that if you lose the ball then you either get it back or buy a new one. The children of the mohalla were fed up with two things in life – first, the government well and second, the house which belonged to Arvind Singh.

There was some possibility of getting the ball out of the well, only if Dheeraj`s mother agreed to lend a rope and a bucket. She would often refuse and say “Ye ladka log bahut harami hai. Ball pehle naali mei girata hai phir kuan mei, yahi paani puja mei lete hai. Sab ka sab gandu hai”. She’d call Dheeraj back in and the game would be closed as the wickets belonged to him.

Arvind Singh’s house was a complete mystery. He was the survey officer of our area. He worked in the ECL (eastern coalfields limited). He lived in one of those quarters provided by ECL. Black, curved roofs thatched with tar. Extremely hot in summers and extremely cold in winters. There was no way to sneak in as he had covered the verandah with a green asbestos sheet. All the quarters were Identical, 9 in a row. We were easily able to retrieve the ball from other houses as none of the others had enough cash to invest in an asbestos sheet.

Arvind Singh had a lot of money. People said that he sold the oxygen masks which the government bought for the people in the mines. He left his house at 9 in the morning on his black Rajdoot, the poor man’s bullet. The sound was so loud that everyone knew that he had left for work. His wife locked the door from inside. No one knew her name. She only came out at noon when the municipality turned on the water supply. She’d come with four amulya milk canisters, fill them and go back.

The sound of the Rajdoot was a signal for all of us to come out and set up the wickets. Just meters away from the tap was our clay pitch. Not long enough for a proper match, but we always played short pitch. All the Bihari aunties would come out and sit on the cemented `chabutra’ (a huge brick pavement made around a tree, generally peepal tree) for people to sit and gossip.

The daily power cut in the evening would unite all the ladies again. It was a chance for us to get out of the house and play `lukka chuppi’. During this time the men would go out, meet friends, drink, smoke, play cards and discuss politics. They would return by 7:30 with the grocery and vegetables.

Dusk would fall and the mosque played the aazhan. It was a signal for us to go home, wash up and study as dad would be home any moment now. Snacks were served as we went home. Generally, it would be left overs from lunch with tea, or `chop-muri` (potato chops and puffed rice).

Life was going on very well until we decided to shift to the city. Sripur, our village was not equipped with proper facilities. The nearest hospital was in Ningha colliery. The doctor would only come in his chamber for 6 hours, 10 am -4 pm. if there was an emergency in the night then the patient had to be rushed to the nearest 24-hour hospital, which was in the city, Asansol.

Sripur is divided into two sectors – Sripur bazaar and Sripur gaon which are further divided into smaller mohallas. To name a few, Nazir para, ek number, do number, teen number, railpar, bus stand, teen patiya, new center, kindoliya and area-2. All these names seemed to be like base camps of some covert military operations.

Arvind Singh lives in ‘Nepali Dhawra’. The story behind the name of the mohalla is that one fine winter a group of Nepali people came and settled here they but could not bear the heat in summer, the heat wave was making them sick and so they went back to mountains. In Hindi `dawra` means `to run’. Hence the name `Nepali Dhawra` was given.

The only people who are fond of Arvind Singh are the kabutars in Sripur. Much like Amrish Puri from DDLJ, he’d come out every morning at 5:30 and feed the kabutars. He hated it if we came out to play in the morning. Every time the ball hit the wall, the pigeons would fly off and he’d shout at us.

After a certain point of time he would start throwing random things at us. He’d pick up anything from sticks to stones. But we would be unmoved by this. He’d pour water all over the chabutra and drain it on our pitch. We would then play ‘kabaddi’, ‘kith-kith’ or ‘doom-doom—chick-chick’.

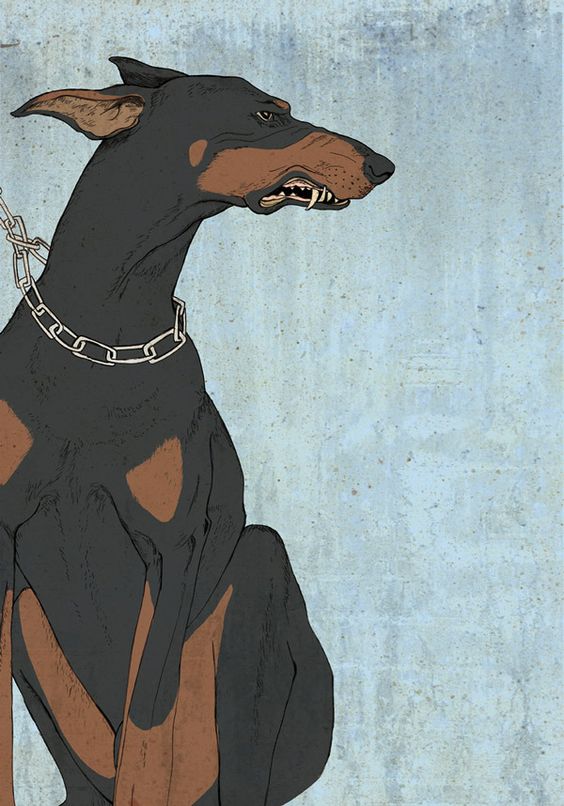

Image credits: Sivan Hurvitz

When he felt that we weren’t going to accept defeat, he’d use the Brahmastra. He’d throw a rubber disc and say “Tuffy Jao”. Tuffy was his 2-year-old Doberman who would bite anyone who took his disc. Rumors had it that Tuffy had bit his master`s wife once when she couldn’t find his bowl and therefore had thrown grains of pedigree on the cemented floor.

Chuniya who had been working in that house for a long time said that Tuffy was too tough to joke with. Arvind Singh deploys this weapon of mass destruction on anyone whom he doesn’t like. “He deployed it once on me when I ate a Marie whole grain biscuit which he had bought for Tuffy”, said chuniya.

He has done the same with Chotu Dhobi who lied about washing clothes with Damodar water when he actually used water from a pond. But everyone knew it as he lived on the road to Joda Talaw. Joda Talaw is another area in Sripur which got its name because there were two ponds — one bigger than the other, situated right next to each other. They were divided by a narrow stretch of land.

The Sripur committee once decided to break the narrow pathway and merge the two lakes, but Chotu was against it as his house was on the pathway. Even though his house was not larger than a 6”4’ bathroom.

Last summer Tuffy attacked Birju mistri, the carpenter who lives beside Arvind Singh`s `chala` (Chala is a storeroom outside the house) He had thrown an empty fevicol canister at Tuffy as it was peeing on the door step of his house after which Arvind Singh declared war against Birju mistri. He still has the mark from Tuffy`s incisors on his right ankle. Yet Arvind Singh does not take responsibility for any of this.

We hate him for some genuine reasons. On the 67th Independence Day, we bunked school and went to swim in a nearby quarry. The quarry was deemed dangerous as many of the villagers had lost their lives either while swimming or while trying to help the one who was drowning. Mochu, Deepak, Jhaikya, Moni, Chunnu and I were having a beautiful day until Mr. Singh wrecked it. He came there for a routine inspection, and finding us there, he called Deepak`s dad and informed him about our little escapade. All of us were reprimanded, belted by our parents.

After that day, we only swam in a pond near the ‘Murabba factory’ (Murabba is a popular fruit that is candied apple, apricot, gooseberry, mango, plum, and quince. It is said to have medicinal properties.) The pond was not that big but was deep enough for us to dive in from the branches of a ‘Junglee jalebi’, hanging over the pond.

Nowadays Arvind Singh is my father`s best buddy, well I can`t believe that because I remember them fighting every day. In 2002 my father won the ward elections for Communist Party of India (Marxist) but Arvind Singh did not like that. People say that he had connections with the congress candidate but he denies it. He also denies his 12-acre property in Kolkata which he received as a gift from Ashok Singh, the congress candidate and coincidently his brother in law.

My dad sued them both. Arvind Singh had to resign from the position of general manager of the Sripur colliery. Further investigations were carried out and Arvind Singh was found guilty of stealing coal pillars left underground to support the earth above it. The government ordered a complete shutdown of the area. He lost the case but was never jailed, he bribed the cops and they came to our house at 2 in the morning for a raid.

Arvind Singh knew that my uncle owned a few illegal arms. Two desi Katta’s and one brand new semi-automatic glock 17 pistol.

My dad made a few calls and somehow stopped them from entering the house. The revolvers were thrown in the quarry and my dad got a legal license for the glock. Years later my dad left politics and entered the Real Estate. Arvind Singh somehow managed to secure a job in the Ningha colliery as a survey officer.

My dad was buying land near the colliery but he needed the signatures of the survey officer. Somehow, they started talking and now every evening one can find Arvind Singh sitting in my father`s shop, sipping ginger tea and discussing politics.

Akash Sharma

Latest posts by Akash Sharma (see all)

- Tussling with Tuffy - 24th April 2017