Filmmaker Hansa Thapliyal was at the Social Justice Film Festival organised in May 2022 by Nous – the association of news arts and film at St. Joseph’s University. Zenovia A Hujon writes here about how this film about two doll-makers reminded her of her grandmother.

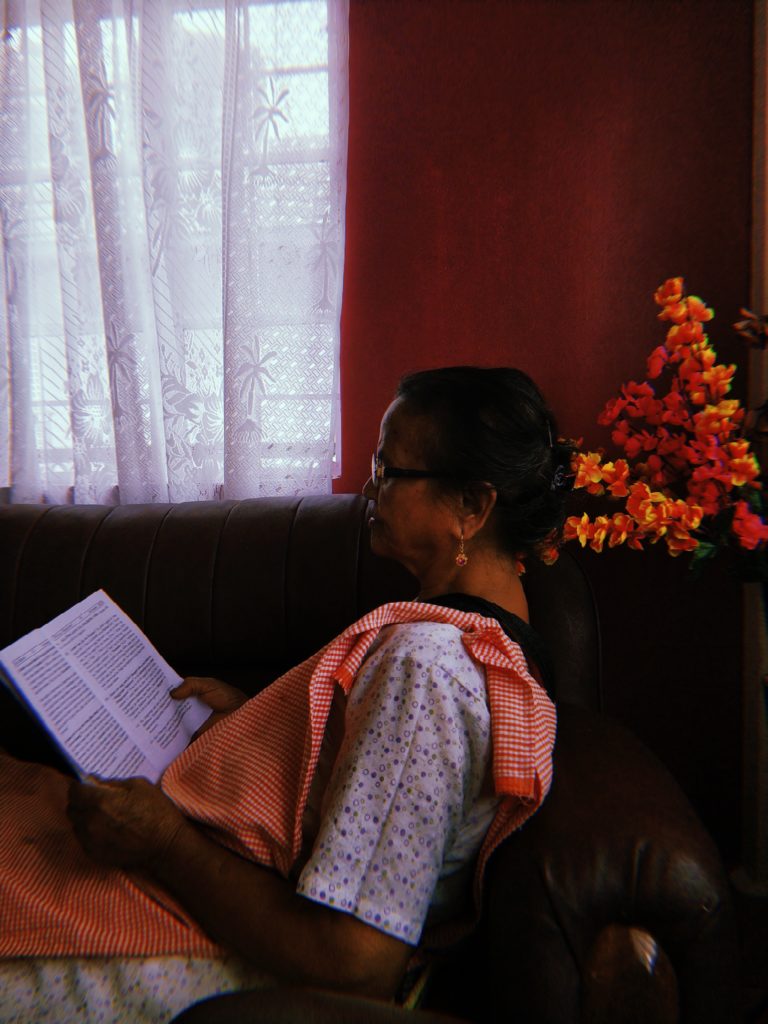

My grandmother, at 74, sits in the sun, braiding the threads of a Dhara while watching a virtual tour of a Japanese town on YouTube. Her wrinkled, brown hands know the art of weaving the Dhara so well that they perform mutely while the TV does its thing. Meimei, as I call her, narrates stories to me, telling me she dreams of going to places like that, but how watching an episode of ‘Somewhere Street’ is more than enough for her. The simple task of weaving Dharas gets her somewhere in life and she is happy.

Like her, Hansa Thapliyal creates her art with the help of two doll-makers, Francoise Bosteels & Milan Khanolkar, who take what they love seriously. Taking her own work just as seriously, Hansa changes the mindset of people by presenting a movie of dolls focusing on social justice through themes of dark and light.

“The Outside In”, she calls it. When asked about how she named it, she explains how Milan and Francoise bring life into these inanimate things they have created. With an outside glimpse of what the dolls do, we are able to see what lies within.

The director says, “Jab aap ise banaate hain tabhee ghar banta hai,” which translates to ‘only when you make it, does a home get made’. She explains how there are various migrants in the world but one thing they mostly have in common is a mother. She who makes a home; she who brings love and care to an empty house and turns it into a ‘home’.

Thinking about this, I recollect stories about Meimei and how she moved from the village of Pariong to the city of Shillong and made a home for my mother and her siblings. Meimei came from a poor family with rusted tin as walls in their home, and holes in their ceiling. They barely had proper lodging; there was no chance for an actual toilet to exist, so open defecation was common in that area.

I recall a memory of when I was five and my family and I visited her village. I had to use the bathroom and as a child, I didn’t care where I went as long as I could go. But the place they took me to was just a wood-enclosed space with a wide hole in the ground for a toilet. I remember fearing the hole and thinking how easily I could have fallen into the monthly (or maybe yearly) collection of human excrement.

Pariong had amazing grasslands and Meimei took me to their sugarcane farm where I consumed sugarcane until my stomach was full. She lived there until she got married to my Paieid, who worked as a veterinarian. They first lived in a government-provided quarter and moved to a small house in a hilly area called ‘Lumshyiap’ which translates to ‘a mountain of sand’.

I was their first grandchild and they took care of me like a tag team. Paieid would help me sleep and Meimei helped me study. I am amazed by how she only finished her education till the 10th grade, but she dedicatedly helped me study for hours ever since I was in kindergarten. She told me that she wanted to study in college but she wasn’t able to. She had to drop out because she needed to start working and provide for her family, as well as pay for her younger siblings’ school fees.

After moving, Paieid was the only breadwinner in the house and they struggled a lot financially. So, to ease the family’s struggles, Meimei decided to start a local shop and took up ‘Dhara-weaving’ as her profession in the year 1971, during the Bangladesh War.

The handwoven Dhara is a well-known Khasi attire that women in the Khasi community wear. It is made of hand-spun Eri, which is a type of yarn made of silk with ends that are embroidered with lavish silk threads. The whole process of making a Dhara requires skilful and careful weaving that only professionals can do and they use eco-friendly methods of production like hand-weaving. Meimei trained herself by watching older women do it. Soon, she was a professional in the art of weaving Dharas. One Dhara took over two weeks to weave and she earned only 150 rupees per Dhara.

Despite Meimei’s low wage, nothing hindered her hard work, she actually enjoyed the art; much like the dollmakers in the movie.

The film began with the words “The Outside In” seemingly embroidered on a newspaper banner, hung on a tree, silently following the directions of the wind. Francoise from Belgium, takes the stand to talk about the challenges faced by Dalit people in the society through her dolls.

I observed Francoise’s hands sewing the dolls together and thought of how I watched my grandmother braid the ends of a Dhara every day. It was just her hands, and a pair of large scissors I wasn’t allowed to touch, some needles, and a comb to brush through the smooth threads. The bright colours of the Dharas could not compare to the vibrancy of the woman who wove them.

However, this sight slowly began to disappear as Meimei became older. Paieid died of cancer and Meimei suddenly had five grandchildren to babysit by herself. The Dhara in her hands disappeared and was replaced by an orange Hot Wheels track. However, I can’t remember the last time Meimei scolded me. She has always been very kind to me and though she wasn’t always very affectionate, she introduced love to me in many ways.

Similar to how Meimei’s life changed, the movie also took a drastic shift in narrative. We get to see a glimpse into Milan’s life, creating a darker atmosphere when she speaks about the ‘Andhaar’, or the darkness. The director made multiple iterations intentionally. She made use of different cameras for different shots. She explains how she felt when she realized the difference between Milan’s and Francoise’s footages. Hansa felt like a parent who painfully realises that one child is not being given as much attention as the other. She wanted to pay equal attention to both as much as she could, subsequently mixing things up and bringing light and dark shots together. This made an interesting impact on the overall film.

There was a short instance in which Milan recalls her father’s thoughts about her art. He said to her, “I don’t understand… but it’s nice what you are doing.” The first time I presented my paintings to anyone was when I showed Meimei a painting of mine. I don’t remember what I painted, I do not know what I paint most of the time, but I just do it because I feel like it. Every time Meimei sees my art, she always compliments me, mostly in English. Even though she barely knows the language, I always hear endearing English words in her thick Khasi accent. It did and still continues to warm my heart entirely and it feels like a gentle push on my back to keep going forward and make art.

A member of the audience asked Hansa if she connected with the dolls as much as the doll-makers did. She stated how she had some time to look around and play with the dolls when she realized they weren’t just dolls to play with. She developed a connection with them because they communicated with her in a way. Taken apart, they are just scraps of fabric, paper, and rubbish, but when put together they become something. As Milan has said in the movie, these materials do not become something new, they simply take the shape of a transformed image.

A brief scene appeared where the dolls are seen talking, although in gibberish, almost realistically. A group of children is seen having giggly conversations before an old teacher holding a long stick appeared and stopped them. Scenes such as this made them appear more than just dolls. They were made from scrap and trash, but represent little people living in their own world, each having a life of their own.

Thapliyal said, “They spoke to me and I spoke back.” This embodies how the movie was to me. Though I did not speak back to it, it brought forth heavy topics that people should be more aware of. The movie was overall an intimate glimpse of darkness, light, and magic through the eyes of Hansa Thapliyal and the works of Milan Khanolkar and Francois Bosteels.

Hansa meticulously creates an incredible collaboration with the two dollmakers, tenderly building the bridge between the world that lies outside and inside. The connection made between light and dark, along with what is real and what is imaginary is what binds the film together. It showcased what I didn’t know and learning about it through the dolls was a pleasant experience. It helped me realize how people can create art simply to create it, nothing more.

Meimei has now given up her profession due to her old age. Her back pains and old bones prevent her from doing what she loves. Despite all this, you can still find her straining her eyes to read a book, or sitting on the mula to braid the silk threads of her own Dharas simply for her own joy. She brushes through them carefully with a hair comb and cuts them off with the same old scissor that is now dressed in rust. Just like Francoise, Milan, as well as Hansa, Meimei loves her art and lives through it.

Zenovia Hujon

Latest posts by Zenovia Hujon (see all)

- Living Through our Art - 7th December 2022