My classmates and I have been stealing women from a certain VJ for three years now.

Not just any women but women who write, which, if you ask me, are the best kind of women. VJ might disagree with me. Probably because she knows it’s not stealing when she happily opens the door to an all-you-can-eat buffet of writerly characters in her classrooms. But I say stealing because it takes a special kind of shamelessness to convince yourself that you discovered these writers. That somehow, even if only inside your head, what is public is very much your personal.

I discovered Nisha Susan first in VJ’s classroom. Later, I rediscovered her in the stories related by people who knew her; my professors who are her friends, my seniors who had interned at The Ladies Finger, my friends who had actually met her. I know about the time she introduced a friend to Japanese cuisine, about the funny men who unsuccessfully flirted with her at parties, about the one time she gave C (who was interning with her) enough money for auto rides and an ice cream. I sometimes find it concerning and somewhat illegal that I should know so many stories about a stranger.

One year later, I got to meet the actual Nisha Susan. Outside of her writing, outside of everyone else’s stories. And I stood mortified as VJ announced to the world that I longed to touch her. The actual Nisha Susan laughed and extended her arm. I touched it. I did not know what to ask her, so I asked her if she ever cried over boys. She told me that she used to cry over silly boys in autos on rainy days. It consoled me that even Nisha Susan used to cry over boys once upon a time. And I held onto that very specific image for yet another year.

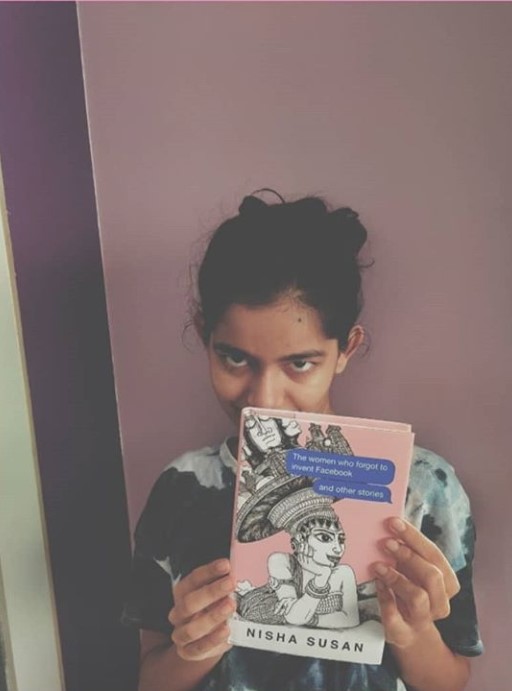

I suppose it comes as no surprise that I pre-ordered a copy of The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories at the first mention of Nisha’s new book on Twitter. I had to get my hands on it before the rest of my classmates did; every other Nisha Susan fangirl that I refuse to acknowledge. It is a strange thing to fall for somebody’s writing. There’s this almost malicious insistence that their writing belongs only to us. You want your every friend and every enemy to read them but you know these stories are specifically yours. Like Nisha herself said, “The truth is that I wrote those stories only for you.”

As I slowly rationed out the stories in her book, hoping to make it last as long as possible, I heard far away cries from the corners of my house, “Neha Susan theerno?” Amma, you know it’s Nisha Susan. “Did you finish your Nisha Samuel?” -_-

The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook and Other Stories is a book about people, some at the cusp of the internet, some others entirely embroiled in it. The strangest thing about the internet today is the dichotomy it insists on preserving. We know people as either good or bad on the internet. But Nisha does this sneaky thing where she injects all her characters- the good, bad and the ugly- with traits that we’ve assigned to the anonymous but good people on the internet. And as far as we know, we are the good people on the internet, aren’t we?

So, it’s often the case that we find ourselves at awkward positions with the people in Nisha’s stories. One second, we’re cooing over two lovers who reunite on Facebook messenger, the world’s most unromantic chat application. The very next second, we watch in horror as Liji’s kuttan turns out to be somewhat of a psychopath. We’re all up and invested in the mystery girl’s romantic adventures on artyhearts.com but feel full embarrassed for her when she reveals much too nonchalantly “I think reservations are really stupid.”

In her stories, Nisha explores the faceless residents of the online world. These characters are like our parents. Occasionally, it strikes us that they’re not so great people but they continue remaining good people or even tolerable people simply because we are forced to know them beyond their prejudices. The opposite also holds true in Nisha’s stories. Falling back on her “chudail-like” instincts, the mother in Missed Call quickly realizes that she has begun to dislike her daughter.

From the almost forgotten pre-Facebook days to the bizarre possibility of a future where women send nudes to online archives, this pink book is like a time machine that hurtles you through the internet’s entire life history. You have singers who meet princes in chat rooms, daughters who only give their mothers missed calls, and even women who need multiple apps to remind them to drink water. Nisha covers all the uncles and aunties and siblings and cousins of the internet’s family tree with frightening accuracy.

Add to this, the ease with which she customises the English language as though it were a Sims character. I like to think that Nisha carries a bit of every city she’s lived in through her writing; the Kerchief Kumaris and comment-adi boys from Kochi, konjum Mother Teresa-type friend from Bangalore, kanji personalities from Delhi and many more.

The Malayali in me felt thrilled when I spotted the Manju Warrier reference in Trinity. When she mentions women who imagined themselves gliding in the long green dress Keira Knightly wore in Atonement, I remembered a forgotten fantasy. Later, I felt amused at how the woman managed to use Dolly Parton’s name as an insult- big haired and over the top.

Characters seem incredibly familiar because Nisha defines entire persons and personalities through that one discernable trait that we often find funny about them. There are no protagonists in her stories because it is difficult not to get distracted by the peculiarities of even the guest appearance-type characters.

It’s an endless list really; the Malayali man whose favourite hobby is to make fun of other malayalees, girls who go to far away towns to torment priests with their scandalous confessions, little boys who convey their little-boy thoughts in old-man language, small town girls with Powerpuff girl superpowers or even writers who worry about their faces being photoshopped for book jackets. Makes you wonder, do Nisha Susan and I know the same people?

I imagine every real-life person who catches Nisha’s eye must go through an intense coconut grating process. Everything about them, she collects into a pile of all revealing coconut shreds and leaves behind a very naked, very brown human shell.

When I first read the cover story The Women Who Forgot to Invent Facebook, all my Nisha Susan fantasies came crashing down. It seemed highly unlikely that I’d ever have a cross-continental map of my sex escapades. Or that I’d ever bemoan the death of a hot, hot, Vilas. It seemed even more unlikely that I’d bring home “a stark naked white boy peeing lavishly into the commode” for my parents to wake up to. Like the girls in her story, I watched and wondered. I had nobody to ask, so I felt slightly insecure and wondered a lot.

A week later, on a Thursday at exactly 7:00 PM, with a guava in one hand and my phone in the other, I was ready at my desk. Nisha Susan was going to talk about her book with Paromita Vohra (another lovely lady I stole from VJ). All fangirls swarmed the comments section of the live stream. Some other shy fangirls (like me) were happy enough lurking. I felt giddy at the oh-so-frenship moment between the women when Paro described Nisha’s “gelusil pink” book as her “antacid to all the unread books” that made her feel guilty. Others chimed in in the comments section with their love for Blouse Mohan from Trinity and innocent speculations about what exactly Radha from Missed Call had mixed into the chapatis.

What is spectacular about Nisha is that the woman squeezes in a story at every opportunity. We were told that her friend KR Meera, who most of us might know as the author of Aarachar, knew exactly what had happened to the beloved Blouse Mohan. What happened to him? Everyone wanted to know. Well, he got married and his wife said, “No more blouses, only salwar kameez.”

Nisha and Paromita laughed at the intellectual gents who could never quite figure out that Teresa, a story from the book, is homage to Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. “You know that no?” she mischievously asked nobody in particular, but looking straight at the screen as though she knew exactly how many of us hadn’t registered this. I felt shy at the other end because much like the clueless gents, I’d never read Rebecca. And as I write this piece, I am becoming increasingly aware of how when we obsess over a writer and their words, we make them our Rebeccas and Teresas. I wonder whether Nisha knows that she’s Teresa to so many of us.

Finally, she said something I wish she’d said all along. She said, “I write stories about people I’m not friends with.” And I heaved a sigh of relief and resurrected my Nisha Susan fantasies. The two women on screen talked to each other with lazy smiles of familiarity. On the other side of the screen, I felt my cheek sloppily but happily balanced on the palm of my hand. Nisha talks about telling stories quickly, before her victims can get away. She talks about the shoulder-gripping pleas of women who want other women to read the things they love so that they can talk about it.

I think about the two women on screen and the many many on the other side of it. I think about the stories, online and offline, that we’ve unintentionally gathered about each other. I go back to the first story in Nisha’s pink book. It’s about a girl who meets everyone else in the world through her friend. And all that these girls want is an audience to be outrageous in front of, to “rehash old stories that only we laughed at.”

VANDANA 3rd September 2020

Loved reading this!

Sindhu 11th September 2020

This was so lovely to read

Anyapa 17th October 2022

Is this you?