Many years ago, I saw Thankan prop up a ladder against the wall of the house. He climbed up and gazed deep into a beehive wedged under the roof. Thrusting a naked arm into the swarm of buzzing bees, he came out victorious- the queen bee captured in a matchbox. “The worker bees always follow their queen”, he sang out to the kids gawking at him from behind the windows. Why must he be so nonchalant in his ways, I remember thinking.

When I was younger, I assumed that Thankan was a member of the All Kerala Coconut Climbers Association. Turns out there’s no such association. Amma was offended when I called him the family coconut climber. “He’s an all-in-all person”, she said proudly.

Thankan glides his fingers across the steel plate and licks kappa and meen curry off them.

He curiously inspects his puckered fingers with fish curry-rimmed nails; his lazy eyes shift to my face. He is waiting for me to ask him something. All I can think of is the Gillette shaving razor ad- the smooth glide of the blade across a stubbly cheek.

Around 10 ‘o’ clock every morning, Thankan and I find ourselves next to each other, on kitchen stools. Him at his second breakfast of the day and me in front of my first. Reena chechi is the only other occupant of the otherwise empty kitchen.

Thankan means the golden one.

In the dining room of my pious, Christian grandmother’s house is a painting of The Last Supper. On it is the silhouette of what resembles a goat, smack in the middle of Jesus’s humble spread. Was the goat invited over to witness important religious history? Or did Jesus and his disciples proceed to devour a main course of mutton biriyani? We’ll never know. Thankan and the goat seem to have lead parallel lives; both unsure about their environment yet integral to it in their stoic existences.

The smell of rubber sheets and coconut husks linger on him. A trail you follow out to his workspace near the well, at the back of the house. It is an elaborate procedure, his work; but I clearly remember pressing my pudgy palm into the rubber milk Thankan left out to set in silver dishes. It is a rite of passage for all grandchildren to leave their imprints on this jelly-like substance; fresh rubber has a peculiar cold and acidic smell to it.

Born Ramakrishnan, Thankan migrated to Kannur district of Kerala with an older brother in the late 1940’s. While the brother returned to their hometown of Palakkad after two years, nine-year old Ramakrishnan, lovingly designated Thanka-kuttan (the golden darling) by my ippapen (great-grandfather), refused to abandon us.

Leaning out of the verandah, my ammama would call out, “Thanka? Thanka?” and soon enough, Thankan would pop out from behind some tree like a genie of sorts. The childhood friends then walked around the house discussing their kutti business of rubber sheets and coconuts, the village gossip intermittently shared between two stooped backs.

Thankan’s ribs are like the wings of an angel, emerging from his crotch, eager to deliver the Lord’s message. His palm feels like rubbing hands over a boulder, its creases and ridges pronounced from years of scaling coconut trees. Callouses on his ankles and wrists tell tall coconut tales, unbelievable acrobatics performed forty feet off the ground.

When the fireflies go to sleep, Thankan wakes up and attaches a flashlight to his forehead. The imitation is a necessity in the darkness before dawn, a mere coincidence that he probably never noticed. The warm, yellow glow helps him cut through the misty darkness- a solitary firefly. It guides him to the rubber plantation where his day’s work begins. Thankan cuts thin spirals around the rubber tree’s trunk, each precise cut ending right above an empty coconut shell. The process is repeated on hundreds of trees as the latex slowly curls down the rubber tree to collect in the shells.

After an arduous few hours at the plantation, Thankan brushes his teeth with a mixture of rice husk ash and salt (he swears on this stuff for his pearly whites). Early risers often walk into Thankan striding to-and-fro at the back of the house, fingers vigorously massaging black-stained gums and teeth. A cup of coffee and five Tiger biscuits later, he is back at the plantation, emptying rubber milk collected in the coconut shells into steel buckets.

Thankan murmurs something about the new dog to Reena chechi. He along with my ammama decided to name it Blacky by virtue of its black fur, for as far as they were concerned, the rest of the world was blind.

Thankan is also famous for his sure-footed descent down wells. The well is home to the many coconuts, buckets, shampoo bottles as well as ammama’s transistor radio; anything and everything we could get our tiny hands on was thrown into the well- for scientific reasons of course. And Thankan would slither down its echoing hollow to retrieve our prized possessions. Although, arrival of his balding moon-head from within the well often meant the rest of the afternoon spent on our knees, heads leaned grudgingly against the well. We returned home after such punishment sessions with red splotches on the canvases of our legs; the artistic endeavors of a Malayalee mosquito.

Five years ago, Thankan bought his first pair of valli-cheruppu. These are slippers you wear in and around the house, when there is no audience to view your admirable shoe collection. There is a sense of liberation one feels while roaming about in their valli-cheruppu. In these trusted comrades, accidentally stepping on shit becomes the least of your problems. Thankan’s pair was no different- navy blue and white Paragon chappals, the raised dots embossed on its surface tickling the toes of your feet. But Thankan hated them passionately. He is a man who, for a better part of his life, embraced nature with all her shortcomings, his hairy chest held high in pride as he strut about life without slippers on his feet.

As a child, Thankan would scramble into my ammachi’s (great-grandmother) cot on stormy nights. Pushing aside her litter of human off springs, the little boy nestled close to my ammachi and winced his eyes shut every time lightning warned him off the arriving thunder.

But he grew up too soon.

Two toddlers on his shoulders and one in his arm. A naughty boy clutched tight in his free hand and two pigtailed girls leading the parade- Thankan made weekly visits to the city with my mother and her many siblings. After the matinee at Kalpana theatre, the group stopped at Gopalan chettan’s tea stall before heading home.

In the summer of 2005, we went home to a very pregnant Ammini pashu in the cowshed. “She moos differently as her date approaches. It is the moo of a mother”, Thankan jokes to my ammama. But he religiously keeps watch over Ammini, serving as her midwife at two in the morning when she finally decides to let her little one out. He cleans out her placenta, bathes Ammini and her calf, and ushers Manikuttan to his mother’s udders. With enough fodder and water placed before the small family, Thankan goes back to sleep for a few hours before he is up again and diving into the plantation.

Amma is right, Thankan is most definitely an all-in-all person.

Thankan lets out a sigh. The fridge is humming tunes to itself. I think he’s bored. Reena chechi’s saree bustles about the kitchen oblivious to our presence. I am now focusing on squishing rice between my fingers. Suddenly, he bursts into a song- this is not unusual for Thankan but it takes us by surprise nevertheless. He wiggles his ears and shakes his head at me. Even his songs sound like questions. Do I sing an answer back?

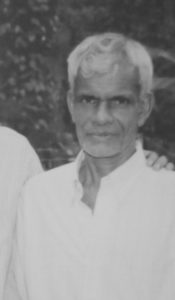

Thankan, 2006

Featured Image Credits – Sreejith Kenoth Via Flickr

Nikhita Thomas

Latest posts by Nikhita Thomas (see all)

- Do Nisha Susan and I know the same people? - 3rd September 2020

- Slaps hard? Not yet - 3rd May 2020

- All-in-all -Thankan - 25th January 2018

Raju Thomas K 27th January 2018

Excellent writing….. enjoyed reading it. How could you capture the nuances of life in those days so well …. excellent…someone doing something real in our family…keep it up – perfect blend of reality and imagination.

Thomas 28th January 2018

Good one..gone back to boyhood days…