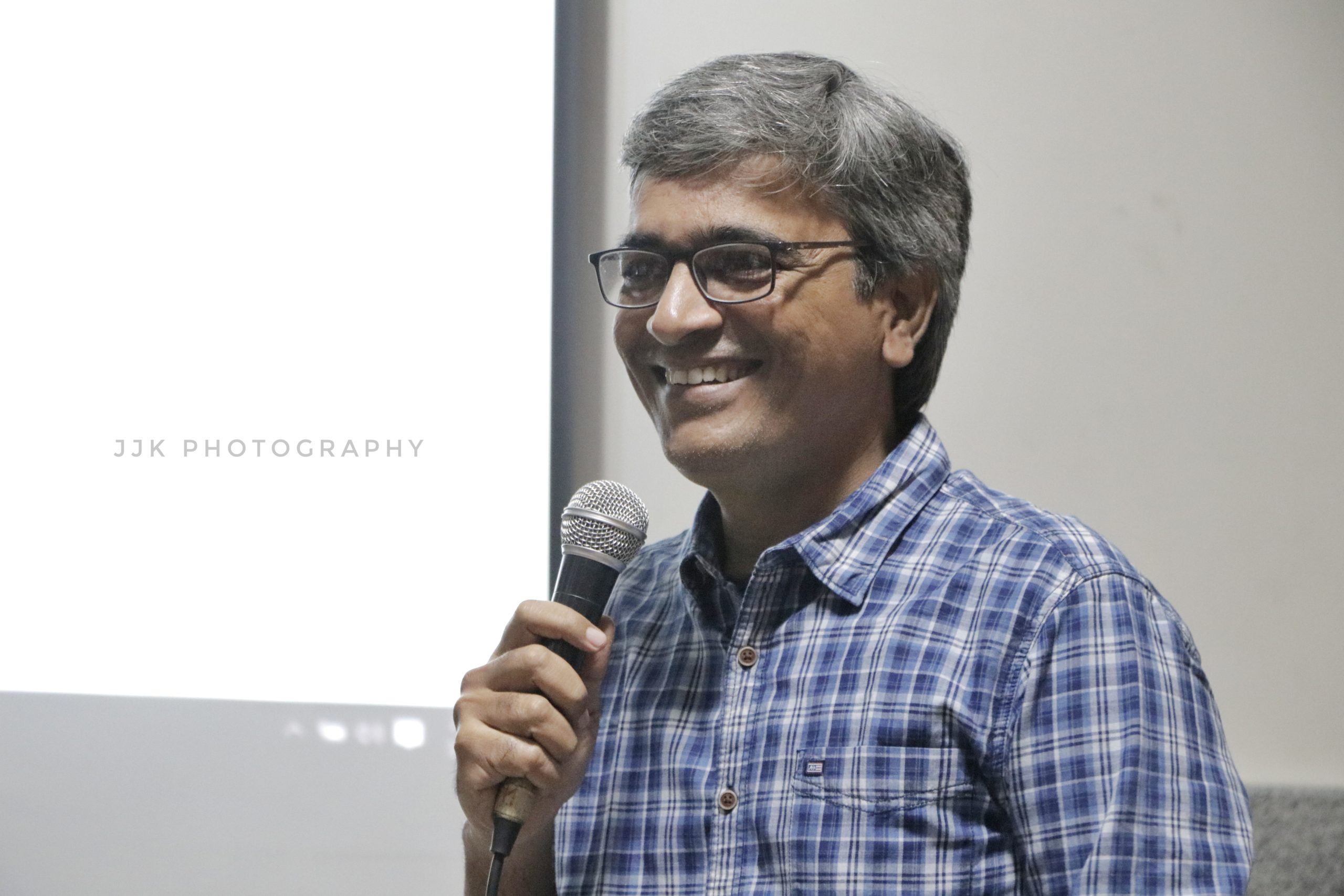

RP Amudhan at the conference, Writing Worlds, Worlds Writing. Image: JJK, @mad_solo_traveller

In March 2020, documentary filmmaker, RP Amudhan conducted a workshop called ‘Frames of Reference’, as part of the conference “Writing Worlds, Worlds Writing”, organised by the Department of English, St. Joseph’s College. Vignesh Kumaraguru, who attended the workshop, writes:

“I’m going to show films which are not issue based or problem based. A documentary per se need not be about a problem, a documentary can be about anything.”

For many like myself in the audience, RP Amudhan has just undone a knot preventing us from understanding what a documentary really is. He has also dissolved my very serious thoughts about attending a documentary workshop. RP Amudhan’s speech is completely absent of discord, he opens up the world of documentaries by carefully removing the word ‘problem’ or ‘issue’ from its definition, and from there segues into what a documentary is, what it means to write a documentary and to write for a documentary.

RP Amudhan is an activist based in Madurai, and his filmmaking is an extension of his activism. His latest film My Caste is a documentation of the experiences of people coming to learn their own caste at various intersections in their lives.

Having reduced the audience’s anxieties to nothing, RP Amudhan manages to have everyone falling comfortably into their chairs and generously handing over their time to him, all while seeming like he has yet done nothing.

He says, “It [a film] talks about an interesting idea that can trigger interesting introspection, journey, and intellectual discussion.” Amudhan speaks of the filmmaker’s ideologue, “That is very important. In any film, it is always that philosophy of the filmmaker”, as the most important tenet, the driving force or motive behind the film and directly ties it to the designing and writing of a documentary.

The first film he screens is Zoo by Bert Haanstra. The film is an interweaving of the highs and lows of a jazz track hand in hand with the chaotic and calming movements of animals and humans in the setting of a zoo. Members of the audience bounce around with the idea that the caged and observed entity in this setting may not be who it seems to be. Another person said, “Zoo has the connotative meaning of the word ‘weird’, like in ‘why are you acting like you’re from a zoo?’, and human beings are most capable of being weird so for animals, we are zoo.”

In the beginning, if you expected to have ‘exposé’ screamed at your face, you will feel like a deflated balloon when you realize that your enthusiasm was misplaced. And when you begin watching the film, you won’t look away from the screen for the fear of missing some tiny detail if you do. You are taken on an aural ride — in each shot, in each scene, and every move in the rhythm, the film is saying something and you are being made to listen to it.

The next film he screens is The Office by Kieslowski, a film that documents the mechanical conversations that happen within a bureaucratic state-owned pension office. The film features those who can operate on nothing but procedure in the face of a million queries – the clerks at the office, and those at the mercy of their patience already with the weight of old age or a personal tragedy hanging over them. This particular film was shot in 1967, but the mechanics and inanity of what it captures is universal. This is where RP Amudhan chimes in, saying “Every space has a language”, hammering the nail in on a point that he pitched earlier.

He screens different kinds of films next, two films by the names Night Mail and And Miles to Go, the former produced by the British General Post Office and the latter by the Films Division of The Government of India.

Night Mail (1936) features the nightly postal train which then operated across the island nation of UK, from London to Glasgow and in its 25 minutes, it documents the unrolling of proper routine procedure by the staff who seem to take great pride in operating it, depicting a clockwork-like image of the train serving the residents of Great Britain. It is supplemented by a narrator’s voice arduously describing the work they’re doing and even features a poem of the same title, which along with the film, went on to become a national staple.

The next film And Miles to Go (1967) was directed by S Sukhdev and its opening frame says

The film is dedicated to all the forces of rational thought

That are opposed to the path of violence

And seeks to strengthen the hands of

Our government in its stupendous task

Of tackling the pressing problems

That face the country

This film features two parallel narratives, one of a couple living an urban and comfortable life and juxtaposing it with the scenes from a slum that can be seen from their balcony. So on one hand, you have pleasant music with a woman combing her hair, and on the other hand, you have pity-garnering morose music with a lady living in a slum going about her everyday actions. Directly implying and shoving it in your face that the government is engaged in the painful task of uplifting the poor, and that it cannot be successful without your support.

This is where RP Amudhan reminds us that this documentary had been written from the very first frame itself. He says, “Reality can give you unbelievable moments which you cannot create and conceive in a fiction film … an important part of writing a documentary is where you have to surrender to nature as a filmmaker. Just wait and record, you do not know what you will get. That is the beauty of a documentary.”

It calls for hard work, patience, and being aptly reactive and responsive. He says it begins with an idea which then becomes something tangible when a crew falls into the routine of what they’re looking for. On the film Zoo by Bert Haanstra he adds, “There is no problem in the film, there is no protest in the film, there is no complaint in the film, it is simply the filmmaker having a philosophical trip.” It is simply waiting and watching that allowed the capture of the language of both, the zoo and the office.

RP Amudhan screens his own documentary next, titled My Caste. The film goes through four parts, filming in a different location each time. It features people telling the story of how they came into the knowledge of their own caste as young children, seeing the divide and understanding which sides of the line they belong to, and how this changes when there are new entrants.

While the characters speak, we don’t see their faces. Instead, the filmmaker shows us scenes from everyday life: scenes of people eating food, playing, laughing, making their hair, making their food, cutting their fish, eating their meat. He tells me he simply asked people a question and gave them time to speak.

He interviews 40 people puts in interviews of only 20, and creates a language of the space he attempts to film. In between observing people in their element and telling their stories, he presents a more fun, nuanced version of the understanding of a documentary that he initially offers, ultimately leaving you with a rich learning experience.

Vignesh Kumaraguru

Latest posts by Vignesh Kumaraguru (see all)

- Documenting Spaces with RP Amudhan - 28th July 2020